FEATURED ESSAY

In September 2021, the Texas Legislature adopted Senate Bill 8, which restricts access to abortion by allowing private citizens to sue service providers. Later in the fall, we commissioned several artists to create responses to the legislation. We opened the series with an image created by the artist Dread Scott that equated Texas governance with the Taliban. Scott’s statement was prompted by the temporal proximity of Bill 8 with the withdrawal of American forces from Afghanistan, as well as the accompanying public debates on the fate of Afghan women’s rights as the result.

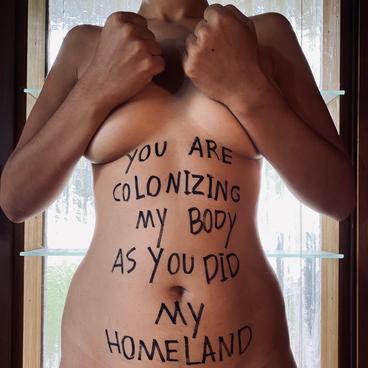

The image, included in both the original version of the series’ opening blog post and on the Weisman’s Instagram page, drew criticism that we came to accept as justified: by drawing such an equivalence we are capitalizing, however unintentionally, on the ages-old colonial trope of the “enlightened” West and the “savage” rest. Then, just a few short months later, Russia invaded Ukraine, prompting a new refugee crisis, new humanitarian efforts—and new criticism of the ways the Western response to this crisis differs from those in the Global South. In the following text, writer and researcher Mariam Banahi responds to the original controversy surrounding WAM’s use of Dread Scott’s image, putting it in the larger context of the highly racialized Western public discourse about “other wars.”

—Boris Oicherman, Curator for Creative Collaboration

Other Wars: Afghans, Violent Care, and Deprived Solidarity

On February 24, Russian President Vladimir Putin made good on his years-long threat to invade Ukraine. Oscillating between disbelief and deep sadness for the violence wrought upon Ukrainians and others ensnared by its borders, many of us inhabit an exhaustion without reprieve. Beginning long before the COVID-19 pandemic, this fatigue is inscribed in how we negotiate the world, exacerbated as it is by the persistence of racialized violence ‘at home’ in the United States and globally. Palestinians, Syrians, Iraqis, Yemenis, Somalis, Afghans, and so many other victims of the Global War on Terror (GWOT)--not to mention the innumerable iterations of US-led or backed regime changes and conflicts–-must continue to contend with explicit, undeniable racism alongside what has become the banal violence of empire.

Late last year, on September 21, 2021, Texas Governor Greg Abbott signed Senate Bill 8 (S.B.8) into law, which prohibits abortion after the detection of a fetal heartbeat and enlists private individuals as part of a pro-life surveillance regime—to report, and even sue, anyone helping those seeking an abortion. Soon after, Dread Scott’s provocative artwork appeared across social media feeds, declaring: “Ruling regime passes law that gut women’s rights and mobilizes society to enforce the law: Texas or Taliban?”. The artwork was later re-shared by the Weisman Art Museum as the part of a series dedicated to artists' responses to Texas S.B.8.

My visceral response to Scott’s artwork was one of annoyance, for the very reasons others might identify: of deploying Afghan women in service to claims of gendered and reproductive violence and patriarchy ‘at home’ in the United States. Positioning the Taliban as the representation of misogyny par excellence appeals to ever-resilient Islamophobia and, rather than subverting the Western gaze, makes a bold statement on its hegemony. The equivalence of Texas and the Taliban, as well as the hold of these narratives and stereotypes, works for many and strikes a compelling chord.

The subtext of comparing Texas with the Taliban–which Scott’s gesture adeptly demands that we interrogate–incites us to reflect on the force and intersections of various discursive regimes, such as Orientalism, Islamophobia, and white liberal feminism. In 2001, the widespread clamor to ‘save’ Afghan women, led by the likes of then First Lady Laura Bush, fanned the flames of war and destruction that ultimately displaced, maimed, widowed, and murdered generations of Afghan women and their kin. Marking the Taliban as the harbinger of women's rights issues plays into the uses and abuses of Afghan women by US empire and its liberal feminist agents. Afghans at home and abroad continue to contend with the overwhelming, unimaginable loss of home and homeland while negotiating a kind of deprived solidarity—coopted into discussions of women’s rights and terrorism vis à vis the evils of the Taliban but hardly ever meaningfully included in discussions of the GWOT and its concomitant carceral and surveillance regimes.

Arguably, with both media and academic cycles synchronized around notions of ‘crisis,’ Afghanistan and Afghans have once again been displaced as global attention shifts to the singularity of the Ukrainian crisis, which is also situated within moments of ‘hope’ through the heroism of ‘everyday’ Ukrainians. This, of course, recalls the panicked abandonment of Afghanistan and the resurgence of the Taliban, which, despite all evidence to the contrary, were sold to us as Taliban 2.0 by everyone from political operatives to media pundits to humanitarians. As the withdrawal and nickle-and-diming of aid to Afghanistan has shown, Afghans are again deemed hopeless, a lost cause, a ‘failed’ community matching the offensive, longstanding designation as a ‘failed state.’ However, it is within the very media framings of Ukraine and Ukrainians that we must call for a renewed, global solidarity across borders and reject parochial imaginings of identity as qualifications of ‘deservingness’—be they based on racialization, national identity, gender, sexual orientation, or something else.

Collectively, those of us residing at the heart of US empire must confront its violences at home and around the world: this is Dread Scott’s artistic endeavor, as he scrutinizes racist gerrymandering, the prison-industrial complex, the brutality of border regimes, and much, much more. For what is art, if not incitement? And what do we lose by demonstrating solidarity with others?

For those of us negotiating the ebbs and flows of interest in the Middle East according to geopolitical maneuverings and calculations of ‘universal suffering’ in humanitarian spheres, the violence of care rears its ugly head at every turn. From the aestheticization of our war-torn landscapes to humanitarians re-casting people-on-the-move as either deserving or undeserving of a dignified life, must we continuously face this violence without respite or limit?

During the long summer of migration in 2015, the inherent racism of border and migration regimes was glaringly obvious to many of us, especially when identifying contradictory treatment between different communities of color. Still others couched their ‘care’ within arbitrary notions of practicality (labor needs and those able to fill them, presumed cultural incompatibility, linguistic challenges, etc.). Now, with the whiteness of Ukrainians added to the equation, the explicitness of racism in Western narratives relative to each population is glaringly obvious, even to those who refused to acknowledge it before. Fortunately, ‘space’ will be made for Ukrainians, as will efforts for their ‘welcome’ and dignified inclusion in the countries which take them in. Unfortunately, our aspirations for a borderless world will once again be deferred; crisis, rather than critical engagement and efforts to rectify the violence of borders, will continue to determine both the limits of our politics and our possible futures. Must we succumb to the world’s injustices and violence without a fight?

Mariam Banahi

Mariam Banahi holds a doctorate in anthropology from Johns Hopkins University. Her first book project, Between War and the World: Afghans, Borders, and the ‘Crisis’ of Migration in Hamburg is an ethnographic exploration of kinship, chronic refugeeness, and everyday life in exile based on over two years of fieldwork in Germany and Kabul, Afghanistan. In 2020, Banahi held a Mellon/ACLS Public Fellows award and also served as adjunct instructor in Culture and Politics at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service. She is currently an independent scholar.