FEATURED ESSAY

Resisting Shame

“It is essential to emphasize that violence against women is a key element in this new global war, not only because of the horror it evokes or the messages it sends but because of what women represent in their capacity to keep their communities together and, equally important, to defend noncommercial conceptions of security and wealth.”

—Sylvia Federici, Witches, Witch-Hunting and Women

I had an abortion.

In fact, I had two.

Both of them ended unwanted pregnancies, at very different times in my life, with men who continued to be my partners, even after we decided not to have a child together. One of these men I eventually married, and after getting married, we had two children.

After having two children, we divorced.

Even though I never felt directly pressured into these decisions about my sexual life or relationships, shame kept me from speaking about my experiences honestly to others.

Shame still makes me hesitate to speak from my experience, even as new restrictive laws were recently passed; even as police and bounty hunters came for women in Texas, just as they’d come for women in other times and places all around the world.

When I was pregnant with my son, I wondered whether I deserved, or was even capable of being a mother. Deep down, shame about having had an abortion made me believe I would eventually be punished — or worse, that my newly born son would suffer — because I’d chosen to have a baby this time, but not the one before. But really, because I had chosen anything for myself.

We don’t think of shame as a law; it has no definable statutes. But shame still regulates our behaviors, used like a weapon to suppress, cage, target, and destroy the autonomy of individuals and communities.

Anti-abortion laws are written and enacted not only through the legal system, but with the shame that many of us have internalized from the church or the state, a shame which we project onto others when we refuse to recognize their humanity, even as we lose ours.

We impose shame onto identities or sexualities that deviate from whatever capitalism and hetero-patriarchy consider the narrow norm: The shame of an unplanned or unwanted pregnancy, including one resulting from consensual sex; the shame of past traumas and their ongoing repercussions; of choices made to survive and to thrive, or of inescapable poverty under the thumb of a sexist and racist economy.

The impact of the war on women’s bodies and our freedoms is collateral damage: Shame aids that generations-long project of asserting control over women and, beyond that, control over a population and labor force that has been conscripted into the service of extractive capitalism.

As feminist author Sylvia Federici traces in her book Caliban and the Witch, control over sexuality and reproduction is critical to controlling a population that is instrumental to the accumulation of wealth for a few—wealth that comes at the expense of the health and well-being of the planet and most living things that depend upon it.

Restrictions on healthcare and reproductive rights disproportionately impact Black, Brown and poor people—especially women and women’s autonomy—but those restrictions also shape the very fabric of our country as a whole.

When sex and reproductive choice are punished through state regulations, such policies ensure that those unjust systems of control over private lives and choices will persist, and that poverty and dispossession will continue as a means of social control. In this system, the health and well-being of women, as well as our pleasure and joy, become suspect. Shame is one weapon with which women are brought under control.

How to resist?

If compassion is the opposite of shame, we can actively cultivate compassion for ourselves and for those experiences that have been previously deemed shameful or deviant.

Abortion is normal.

Even prior to the establishment of medical birth control and abortion procedures performed by doctors, women throughout the world held and transmitted knowledge of their reproductive cycles; they understood the use of plants to act as emmenagogues (stimulating blood flow to the pelvic area and uterus) or abortifacients (terminating pregnancy).

This wisdom— these interdependent relationships between our bodies, plant relatives, life-cycles, and the land—was labeled “witchcraft” and violently repressed by both the church and the state in order to bring about a capitalist economy.

Anti-abortion legislation is not just a women’s issue.

Laws criminalizing abortion, which lead to maternal death and the suppression of female choice and autonomy, are a violation of human rights. By extension, these restrictions impinge upon the health and well-being of whole families and communities.

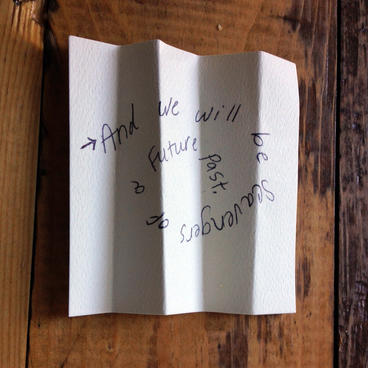

My abortions were a choice I made in order to live more fully, and to escape generational poverty. I wasn’t ready and I did not want to be a mother, then. I am no longer ashamed to speak about it now, because I hope sharing my story can encourage others to find caring and empowering connections. “The conversations we have with each other, the learning, the writing we do ... create a shield against the shame weapon,” write Amy Torak and Risa Dickens in their book Missing Witches: Recovering True Histories of Feminist Magic.

Without shame, we can start to dismantle the mechanisms of power and control that extend from legal, and even social restrictions on women’s bodily autonomy and freedom. To disarm the state, we need to face the role of shame in shaping our relationships with ourselves and one another.

Artists Respond to Senate 8 Bill

On September 1 2021, the Texas state legislature adopted State Bill 8, which allows private individuals to sue anyone aiding women in accessing abortions. We invited some of WAM’s past artists-in-residence to offer their reflections and commentary on this Texas law in images and/or text.

Read an introduction to this series of artists’ responses to the legislation by Curator for Creative Collaboration Boris Oicherman.

Shanai Matteson

Shanai Matteson is a visual artist, writer, and cultural organizer. She lives in rural Palisade, Minnesota, where she grew-up. Shanai is currently working to help organize cultural and community space at Akiing / Welcome Water Protectors, a pipeline resistance camp established by Indigenous women during the movement to stop the Line 3 oil pipeline. As a non-native woman whose family settled less than a mile from Akiing, Shanai sees her activist work here as a kind of service and repair, and a way to encourage a just transition for Indigenous and rural communities in the deep north. As an artist, Shanai creates visual and literary work to honor the complex and interdependent nature of identity, action, material, and memory.