FEATURED ESSAY

AN ACT relating to abortion, including abortions after detection of an unborn child's heartbeat; authorizing a private civil right of action.

(Texas Senate Bill S. B. 8, September 1, 2021)

...starting in the mid-16th century, while the Portuguese ships were returning from Africa with their first human cargoes, all the European governments began to impose the severest penalties against contraception, abortion and infanticide. [...] New forms of surveillance were also adopted to ensure that pregnant women did not terminate their pregnancies. In France, a Royal Edict of 1556 required women to register every pregnancy, and sentenced to death those whose infants died before baptism after concealed delivery, whether or not proven guilty of any wrongdoing. Similar statues were passed in England and Scotland. A system of spies was also created to surveil unwed mothers and deprive them of any support.

(Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Autonomedia, 2014, p. 88)

On September 1, 2021, the Texas legislature adopted State Bill 8, which allows private individuals to sue anyone aiding women in accessing abortions. Shortly thereafter, my social media feed was quickly filled with creative responses by artists across online media in the period following the adoption of the new Texas law. Motivated by this collective creative outburst, we asked five of WAM’s previous artists-in-residence for their reflections and comments on the law.

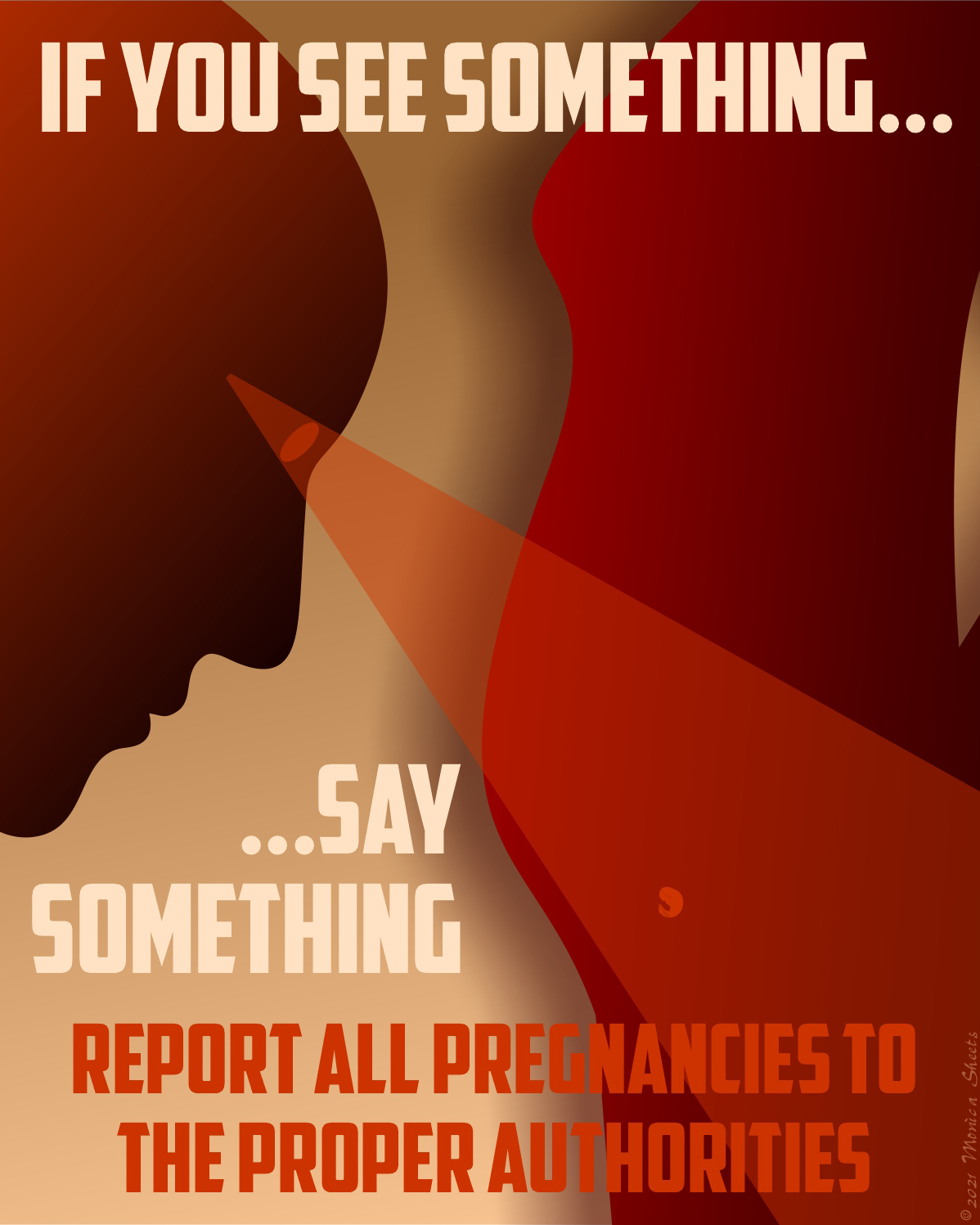

All of them chose to address the subject from an historic perspective. Monica Sheets evokes the experience of working in the former German Democratic Republic, where state surveillance apparatus relied heavily on citizen-informants. Nooshin Hakim Javadi links the present drive to control women’s bodies to the history of colonial control. Candice Davis's response draws on her family history, and the extended kinship between the contemporary African Americans and their enslaved ancestors. Shanai Matteson offers a personal essay about the history of shame as an instrument of control. Rachel Jendrzejewski’s submission, written by an anonymous patient at the Planned Parenthood clinic, sums up this broad historical perspective with a one-line poem:

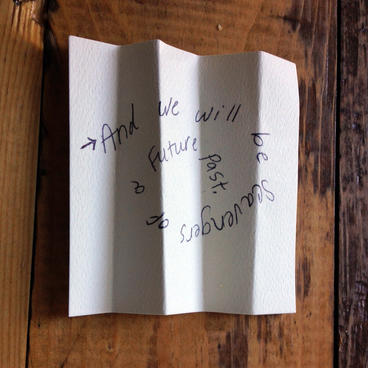

And we will be Scavengers of a Future Past.

In her book Caliban and the Witch, Silvia Federici makes a case for the inextricable link between the development of the new social order in Europe of the Middle Ages and a drive for state control over women’s bodies. In the conditions of rapidly developing early capitalism, when it became clear that its single most valuable commodity would be labour, the powers that be couldn’t allow women to exercise control over the reproduction of that labour force. Authorities established new norms that seized control from women, rendering it unto themselves—but also effectively relegating that once private purview to oversight by society at large. The state and church exercised judicial measures, such as equating birth control with heresy and burning trespassers at the stake as witches; they also worked to establish new cultural norms to enforce control without direct state intervention.

A norm of newly prescribed, socially acceptable behaviours for women began to take root. Behaviours outside of these prescribed limits, especially the exercise of autonomy over one’s own reproductive functions—through use of contraception, sexual practices, or gender nonconformity—were declared to be shameful and worthy of legal persecution and public condemnation.

It is not accidental that these developments coincided with the beginning of European colonial conquest and the opening of the Middle Passage. Acts that were justified by the rhetoric of the value of unborn human life conveniently coincided with the genocidal disregard for life already born, both motivated by the greed of the rapidly expanding extractive economies for control over labour. The external colonization of the overseas lands was supported by the simultaneous internal colonization of Europe’s own cultures—including the shaping of a new cultural role for women’s bodies as a strictly regulated resource.

What, however, is an art museum doing here, delving into scholarly debates and responding to daily political controversies? The answer to this question is, in fact, rather straightforward: museums do it because artists do.

The status of a political controversy does not exempt an issue from moral scrutiny and cultural examination by artists. There is a terrifying thread running through the core of our culture, connecting the medieval witch hunt with contemporary legislature. “Artist” is one profession that qualifies its holder to address issues of culture publicly and in real time. What are art museums for, if not to amplify these artists’ voices?