FEATURED ESSAY

Telling the Story of Kinship

In my time doing research into my family history, I came across allegations that my great-grandmother died as a result of mental and physical health complications after an illegal and unregulated abortion. She’d already faced a lifetime of hardships. She was a social pariah in her small town, due to widespread knowledge that she was the illegitimate product of an affair. Her mother passed before her second birthday and her father’s high-travel job meant he had to leave her to be raised by his sister and her husband. My great-grandmother was subsequently impregnated by and married to her adoptive parents’ (her aunt and uncle) son, who was 20 years her senior. She remained married to her cousin for almost a decade. Two years after his passing, she found herself pregnant, embroiled in a battle against her family members’ religious convictions about extramarital intercourse. As a Black, single, working-class woman in Texas at the time, her options would have been limited. She died in flight, on an airplane shortly after having had an abortion. There’s no way to know for certain whether or not her lethal post-procedural plane trip was intentional or accidental, but oral histories in my family imply that my great-grandmother knew of the danger in flying with such an advanced case of toxemia.

My great-grandmother’s story from 1950s Texas reminds me that the disproportionate safety risk for People of Color in the creation of anti-abortion laws is nothing new. Marginalized people often have more to lose with an unplanned pregnancy. Beyond the risk to their finances, there is also the threat to health, the threat of losing community.

According to reporting by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Black women have consistently experienced abortion at a rate four times higher than that of white women. Violation of abortion rights has a greater influence on communities already endangered by lack of access to reproductive health and medical care, as the CDC also reports that “Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native women are two to three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women.” The disparity in care is longstanding and historically rooted in colonialism. A struggle for reproductive rights was not only something I shared with my ancestors; it’s also something around which I found contemporary community.

I first became interested in my family history after being introduced to the notion of personhood as communalistic. That concept allowed me to consider, for the first time, how my identity had been influenced by the inheritance of my parents’ and subsequent ancestors’ ways of being, teaching, and internalizing culture. In his interview with Zora Neale Hurston, Kossola “Cudjo” Lewis, one of the last known survivors of the Middle Passage, remarks that he cannot tell his story without first telling the story of his father and grandfather. Cudjo, who represents a direct line of cultural connection between West Africa and Enslaved Black America, embodies a multiplicity of self, as he calls upon those before him in order to tell his own story.

With this understanding of composite personhood, I became particularly absorbed with the idea of transgenerational trauma. Research on transgenerational trauma not only acknowledges the learned traits we inherit from our ancestors, but also implies an epigenetic change based on the experiences of our predecessors.

With five generations between myself and my enslaved ancestors, I look at the ways their experiences are manifested in my identity through the African Diasporic understanding of my personhood, via the concept of Ubuntu as it is characterized by Dr. John Mbiti: “[a]n individual person does not and cannot exist alone, only corporately…;” Acknowledging that “[a]n individual’s existence is owed to past generations, as well as contemporaries;” Remembering that “I am, because we are, and since we are, therefore I am.”

One might also recognize the role of “fictive kinship”— familial bonds between people of no blood relation—in the African Diaspora. We understand the greater Black community as an extension of our family. This becomes an important way of understanding “family,” particularly during slavery when the survival of or proximity to our blood relatives was not guaranteed. By acknowledging the experiences through which we relate to one another, we continue to operate within Ubuntu. (It’s something now evident in social media, through the creation of online communities, like “Black Twitter.”)

My own understanding of my personhood has evolved not only to recognize myself as a fraction of my family’s history, but also as one part of a contemporary social community. Responsibility for the well-being of our community is part and parcel of bearing responsibility for the well-being of ourselves. Especially in the West, it’s easy to narrow one’s interests to only consider what we, as individuals, do or do not have access to. Many of us have been indoctrinated with the idea that everything we have is a reflection of personal hard work and morality. Much more difficult is the realization that social welfare is beneficial to every individual—the idea that everyone’s being guaranteed access to their basic needs makes our society safer than any threat of consequence. Proof of this can be seen in the continued patterns of incarceration and houselessness. A system reliant on punishment does nothing to eliminate the social issues at the root of houselessness, crime, or carceral discrimination. By contrast, a sense of community and care for one another gives political power to ordinary citizens. It allows us to stand as a united front and demand our government’s involvement in the support of social programs.

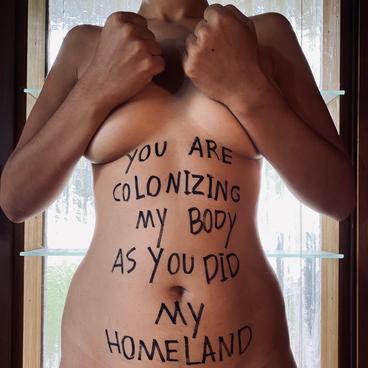

With the recent creation of the Texas “Heartbeat” Act, it is crucial that we invoke compassion for the part of our community living in Texas. Amidst the comparisons to dystopian novels, we must also recognize that there is work to be done. Even an unpopular public opinion has a tremendous political impact. It is essential to engage with our community members whose ideas differ from our own. As an artist, my role in the community is creating physical or visual forms of communication that engage people with their community and its history. Giving people a tactile connection with the experiences of others can help inspire an empathy they might not feel otherwise. As people living under capitalism, it is easy to prioritize our experiences as individuals. We overcome alienation by reinforcing our sense of community. It’s easier to communicate with the people you are in community with, the neighbors whose names you already know and with whom you share discussions. A competition-based economy tends to isolate us from one another. Our struggle just to live distracts from the things that actually connect us and give us a sense of community. It is important that we learn to struggle together, without diminishing any individual’s sense of identity.

A collective response to social issues is what forces real change. We can see it through the power of a community of workers, striking together for changes in wages or working conditions. We continue to wrestle with the same issues regarding abortion and healthcare, decade after decade, because we haven’t fully realized how to unify a larger community behind the fight for effective social programs. While mutual aid efforts, both in the 1950s and today, serve as excellent ways to mitigate these issues for people on a more individual basis, true social change can only be won with a broader unification of community in the struggle towards healthcare. When we recognize the challenges of our community as our own, we are more successful in coercing progress that can break the cycle of struggle for marginalized and working-class people.

Artists Respond to Senate 8 Bill

On September 1 2021, the Texas state legislature adopted State Bill 8, which allows private individuals to sue anyone aiding women in accessing abortions. We invited some of WAM’s past artists-in-residence to offer their reflections and commentary on this Texas law in images and/or text.

Read an introduction to this series of artists’ responses to the legislation by Curator for Creative Collaboration Boris Oicherman.

CANDICE DAVIS

Candice Davis is a conceptual artist from San Antonio, TX, who is now based in Minneapolis, MN. Her work primarily focuses on digital media, installation, and performance as a means of witnessing for the trans-generational experiences of marginalized people. Read more about her project as an artist-in-residence with WAM's Target Studio for Creative Collaboration.