FEATURED ESSAY

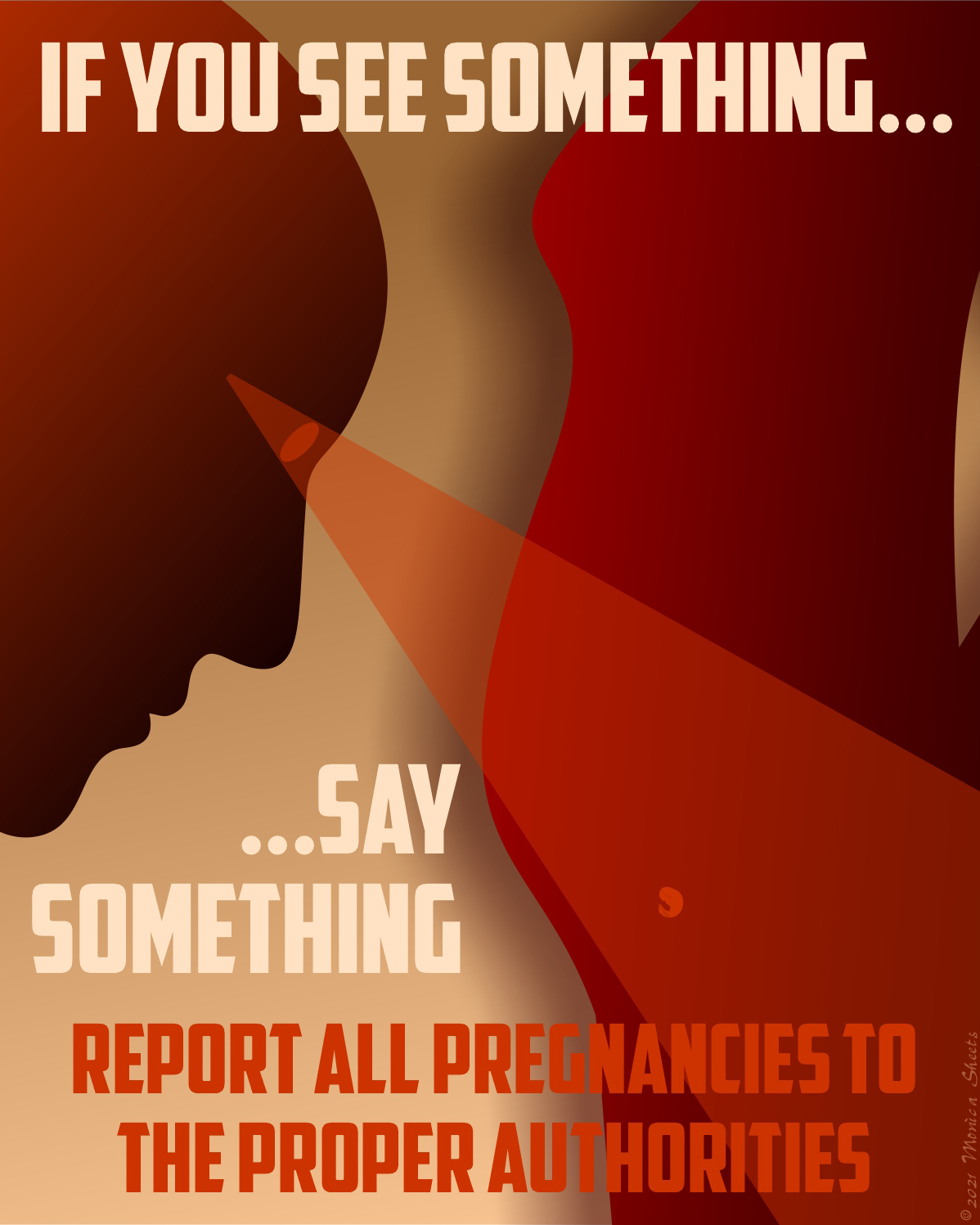

It’s fitting that Texas’ new abortion restrictions went into effect during the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attack in the US. 9/11 and the subsequent, unending “War on Terror” inaugurated an era of surveillance that now seems inescapable. Technologies like facial recognition software have made possible the kinds of observation and social control that were once the province of dystopian fiction. But what’s most insidious about the Texas law is its reliance on peer-to-peer surveillance and unofficial informants. A constitutional challenge would have been necessary to enact this level of restriction through criminal law enforcement and the state; instead, Texas has created a civil system of incentives for people to inform on one another.

I spent seven years living in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), working on community projects that dealt with the aftermath of a society in which state surveillance was rampant. For many, the GDR Ministry of State Security (colloquially known as The Stasi) felt like an omnipresent and omnipotent force in their lives, influencing job and educational opportunities and even interpersonal relationships. The Stasi’s most powerful tool was not technology, but rather unofficial informants—your neighbor, your relative, your coworker, your spouse. The Stasi could only have dreamed of offering the monetary incentives to informants that Texas is. Of course, in Texas, the state is not directly providing the funds, but rather merely enforcing their “recovery” from a party found guilty.

But monetary gain is not the only form of reward, in the GDR or in Texas. Many were and are happy to inform because of their ideological convictions, not pausing to think about the greater societal implications of their actions, or how they might serve to undermine faith in the government. The GDR constitution guaranteed civil rights that were similar to those in the US constitution. The blatant, often arbitrary flouting of these rights created a distrust of government and disaffection that led to what was called the “niche society”—a retreat to the personal and private and disengagement from the public sphere.

I don’t make comparisons between the US and GDR lightly or as an attempt at hyperbole. Since my return to the US, it has become difficult to ignore the increasing societal parallels. As in the former GDR, the widespread distrust of government and retreat to niche societies in the US has been accompanied by a rise in political extremism from a minority and increased political apathy from the majority.

The Texas law is both a symptom and an exploitation of these trends. In circumventing the Constitution and delegating prosecutorial power to the individual, State Bill 8 makes the same mistake as was made by the Stasi, and it’s a misstep that undermines governmental legitimacy. The deputization of the civilian population only increases societal atomization, exacerbating the crisis of democracy in which we already find ourselves.

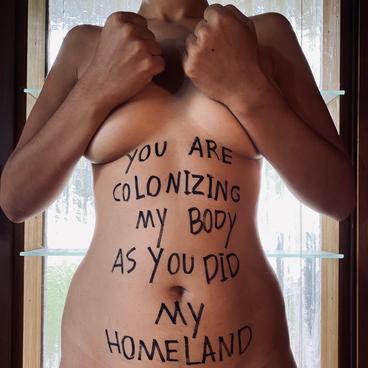

Artists Respond to Senate 8 Bill

On September 1 2021, the Texas state legislature adopted State Bill 8, which allows private individuals to sue anyone aiding women in accessing abortions. We invited some of WAM’s past artists-in-residence to offer their reflections and commentary on this Texas law in images and/or text.

Read an introduction to this series of artists’ responses to the legislation by Curator for Creative Collaboration Boris Oicherman.

Monica Sheets

Monica Sheets creates platforms for communication as a means of civic engagement for herself and other participants. She was born in Toledo, Ohio, and her experiences growing up in America’s Rust Belt were pivotal to her decision to work directly with participants, coming from a desire to reach audiences who might not normally visit galleries and museums.