FEATURED ESSAY

the wider you are

the emptier and the more

innocent of any

signal the more

precious the text

feels to me as I make

my way through it reminding

myself listening

for any sound from you [1]

—From To the Margin, W. S. Merwin

The speaker in W.S. Merwin’s poem, To the Margin, addresses the margin on a page, that hardly noticeable blank space surrounding the text, using the second person, “you,” as if the margin were the speaker’s wise friend. This poem resonated with me as I (poet), with my colleague, Dr. Angie Mejia (sociologist), prepared for the creative writing workshop for COUNTERSPACES: BIPOC PASTS, PRESENTS, AND FUTURES IN MEDICINE. Like the poem, the workshop asked us to notice the seemingly blank spaces and to listen for “any sound” from the margin.

Dr. Mejia and I teach at the University of Minnesota Rochester (UMR) for the Health Sciences program. Since April 2021, we have been offering a series of creative writing workshops, entitled "Counterspaces." Counterspaces are defined as "safe social spaces...which offer support and enhance feelings of belonging”[2] in marginalized individuals who exist in spaces not made with them in mind. This project began as a response to the stories of the BIPOC students at UMR who expressed their distress as they witnessed increasing racialized violence, hate crimes, and social injustice, while navigating the global pandemic. I could see that the students held mixed emotions and thoughts; mixtures tangled into tight balls inside them. They didn’t know where to begin or how to explain their anger. Counterspaces’ intention parallels that of the speaker in Merwin’s poem: to listen to any stories, perspectives, and voices of marginalized community members pushed aside into the tiny space of the margin.

Listening is the first step to bringing such stories to the center. But centering requires additional work to make the invisible visible. We applied the processes of listening and centering to our recent workshop, Counterspaces: BIPOC Past, Present, and Futures in Medicine. We discussed whether the BIPOC members from the biomedical field had the opportunity to express their lived experiences openly. The workshop focused on shedding light on the invisible stories in the history of medicine. For instance, we read a doctor’s notes from 1855 itemizing his economic loss, in which he counted “two negroes and three horses,” revealing his dehumanized perception of slaves.[3] We also read the recollections of formerly enslaved individuals, who described enslaved persons tapping into their traditional herbal healing methods so effectively that white people sought their help for healing.[4] The general public is not aware of such role reversals, especially the wisdom of enslaved individuals. Listening to voices from the past was a way to invite, through a series of creative prompts, BIPOC participants in this workshop to reflect on their own experiences: the experience of being silenced and the truth they want to illuminate. We shared our writing and thoughts among the group and listened to each other.

Poster-making followed writing, tapping into the techniques introduced in a recent outdoor exhibition, Just Yesterday, in which bold and colorful posters that included pop culture icons invited contemplation of systemic injustice. We talked about the power of reference such as the power in comparing two historical facts side by side in the World Wars poster.

The first fact, that Black Americans weren’t allowed to play Major League Baseball until 1947, is illuminated by another fact, that Black Americans were asked to fight and die for their country in World Wars I and II. The boldly visual juxtaposition of these facts demands attention and reflection from viewers. Inspired by this approach, we invited BIPOC participants to reflect on their own and their community’s stories, asking them to select a story to shed light on and to identify what they wanted the majority to really see.

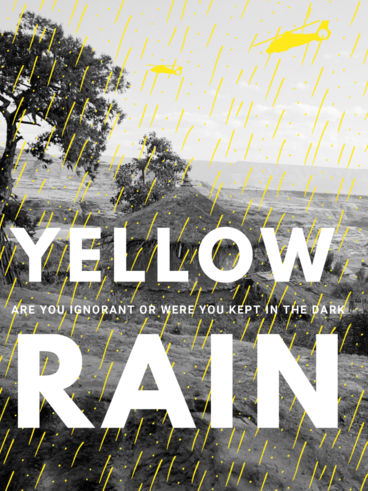

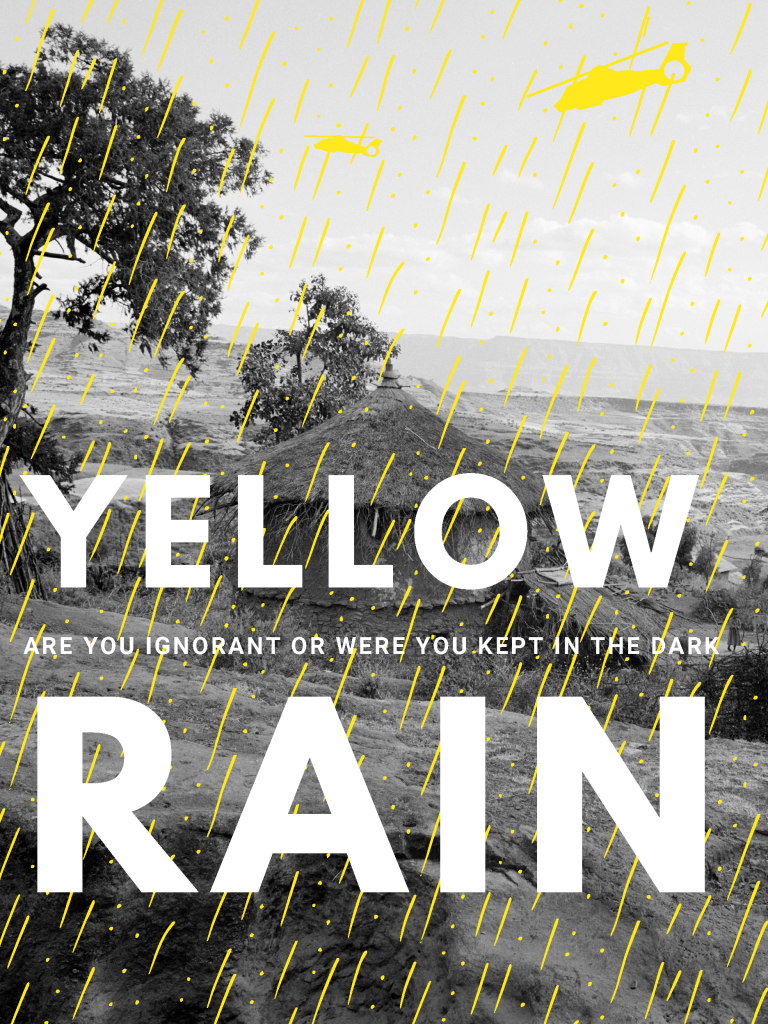

Selecting a story is, in itself, a person’s story. It shows what story they came from and what matters most. Yellow Rain, created by one of the participants, Kao Moua, a third-year Health Sciences student, reveals exactly this issue: what matters to her and the larger story of why this story was pushed aside.

Agent Orange, the U.S. military’s chemical and biological weapon that impacted millions of Vietnamese between 1961 and 1971, may be known. But yellow rain, the oil-like substance that fell on the villages the Hmong people were evacuating, is not taught in history classes in the United States. Many Hmong fought alongside the Americans during the Vietnam war, which put them in a vulnerable position after the U.S. military’s departure. Diverse theories exist about the composition of the yellow rain, but the critical message Moua delivers through this poster is that none of the Hmong people’s experiences—the secret war, yellow rain, and the compromised position of the Hmong people—are known to the people in the United States. “Are you ignorant,” she asks, “or were you kept in the dark?”

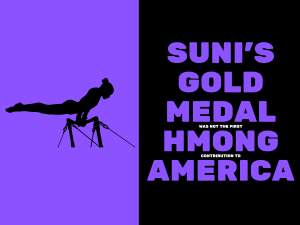

Relocating the center of the story, moving it from the margin to the text, can become an entryway to exploring how society selects what stories to be centered. Kylie Pha, a fourth-year Health Sciences student, painfully captures this question through Suni’s Gold Medal.

Pha explains the irony that it was not until Suni Lee won gold in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics that awareness of the Hmong’s marginalized and vulnerable status became known to the general public. Drawing attention to the decades-long gap between the Hmong’s support for the U.S. during the Vietnam War and Lee’s gold medal, Pha brings to the center of the page the silencing and alienation of those whose contributions are marginalized.

As I reflect on the workshops and participants’ creations, I am reminded how many sounds are in the small space of the margin. Merwin’s poem ends with a reminder to listen to the blank space that looks empty, but is not. For BIPOC individuals whose stories are relegated to the small space in the margin, there is a need to be bold, add color, and find a way to persistently speak. We may be tired. But we owe it to our BIPOC ancestors who have navigated their own difficult times, who did the most important work of surviving, leaving us with stories, information, insights, and courage.

[1]Merwin, W.A. (2005). Present Company. Copper Canyon Press.

[2] Ong, Smith, and Ko, “Counterspaces for Women of Color in STEM Higher Education: Marginal and Central Spaces for Persistence and Success,” 207.

[3] Washington, H. A. (2006). Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present. Doubleday Books.

[4] Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project (WPA) – Former enslaved African American Interviewees (1936-1938). As cited in: Bronson, J., & Nuriddin, T. (2014). I don’t believe in doctors much”: The social control of health care, mistrust, and folk remedies in the African American slave narrative. Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences, 5(4), 706-732.

Yuko Taniguchi

Yuko Taniguchi is a poet, novelist, and a creative collaborator who explores the intersection of healing and creative process with writers, artists, and healthcare professionals. She is currently developing practices that promote engagement, compassion, and inspiration for adolescent patients in the Acute Care Inpatient Psychiatric Unit for Children & Adolescents at Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, MN. Taniguchi’s program at Mayo Clinic began by giving adolescents who struggle with mental issues the opportunity to participate in creativity-based activities and examining the responses.

Taniguchi is a faculty member at the University of Minnesota Rochester and Mayo Clinic Humanities in Medicine.

Counterspaces workshop

The Counterspaces workshop is dedicated to providing a safe and welcoming space for members who self-identify as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC, including those claiming multi-racial identities) to reflect, express, and share their own stories through creative writing and poster making. This two-hour workshop was led by Dr. Angie Mejia (sociologist) and Yuko Taniguchi (poet).

This workshop drew inspiration from Just Yesterday, an outdoor installation which was on view at Weisman Art Museum through Oct. 1, 2021. Workshop participants were invited to offer reflection and contemplation of systematic injustice through bold and colorful posters that contain iconic pop culture references, and Counterspaces at Rochester Art Center, a collective healing project for Rochester community members who have been impacted by the existing and increasing acts of racialized violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC).