FEATURED ESSAY

Imagine two faculty members at a university in the US Midwest. One is a Japanese-American woman and one Latina. One works with social theory and the other works with art, psychiatry, and medicine. They work to teach and research like any of their peers — maybe even harder — and have the added labor of emotionally supporting Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) students on our campus, which make up 40% of the total student body. These two faculty members have been listening to and comforting BIPOC students who feel distressed due to COVID-19 and stressed at being BIPOC in a place and in a moment White people are not dealing well with the consequences of societal oppression from which they have benefited. I am one of these faculty members. My colleague, Professor Yuko Taniguchi, reflects on this experience in another post. We hope that our posts for WAM encourage discussion of how art, health, and museum practice might intersect to influence and transform our communities.

Our earlier project, Counterspaces+Art, began as an idea fueled by the sense of pain and concern that I and my colleague shared for our students. A day after the Atlanta spa shootings, Yuko wrote a beautiful poem and reflection on silence—the silencing of BIPOC voices, but also the silence of White people when reflecting upon incidents of racialized violence. She suggested we host a gathering for our students of color. But this gathering needed to be more than just the usual safe space to talk; it needed to be an opportunity for these students to share their experiences and authentic truth openly and use their pain as activism. “We need a counterspace!” I almost shouted. “With poetry!” I recall Yuko responding via text message.

Building a counterspace is a practice of resistance and transformation nurtured by and geared to racially marginalized individuals (Yosso and Lopez; Grier‐Reed). Counterspaces, as defined by critical race theorists and other scholars, serve as spaces for BIPOC to seek support and validation of their experiences with oppression and to develop cognitive strategies to survive hostile social environments (Yosso; Yosso et al.; Solorzano et al.; Case and Hunter). For our University of Minnesota Rochester (UMR) students, there are no spaces or practices geared for them to feel empowered enough to discuss their experiences with racialized violence, including microaggressions, in a transformative way. Yet these students were navigating multiple spaces and dealing with experiences that were negatively impacting their emotional well-being.

Referring to it as the Counterspaces+Art model, Yuko and I envisioned the possibilities of artistic creation and creative writing workshops, using the works of feminists of color like Anzaldua, Lorde, Yosano Akiko as inspiration, to build a counterspace for UMR BIPOC students. The artistic products that emerged from these first workshops are now at the Rochester Art Center.

Counterspaces: BIPOC Pasts, Presents, and Futures in Medicine

Since counterspace building is both a strategy and response to experiencing interpersonal, institutional, and structural forms of oppression, including gendered racism, Yuko and I believed that our approach to counterspace building, specifically via the use of art and empowerment praxis, could be helpful for those experiencing uniquely localized forms of interpersonal, institutional, and structural forms of racialized oppression. This practice is especially powerful for those with no access to spaces, resources, places, or people to safely discuss and find ways to change and respond to these experiences.

Our role, as counterspace conveners for the Counterspaces: BIPOC Pasts, Presents, and Futures in Medicine workshop, was to offer space for BIPOC in healthcare contexts (students, professionals, and even patients) to build theoretical connections that places our histories, our languages, and our cultural knowledge as valuable strengths. The workshop’s focus would be on how pasts in medicine and health continue to manifest in some form or another in the present and what our roles as providers, patients, educators, and members belonging to racially marginalized communities could look like in the future. The first step was for all of us, facilitators and participants, to reflect on the common societal misconception that imagines medicine and healing to be value-free and apolitical practices, noble ventures even. These views are not only held by some of us outside the healthcare and medicine field, but also by many inside them. To engage in a practice of “talking back” (hooks) to this important aspect of medicine, we went to the historical record to highlight the very intentional and visible role of the physician, as an individual, and medicine, as a discipline, as inherently connected to the perpetuation of racial violence, including indignities of the transatlantic slave trade (Washington).

Yuko and I would not just emphasize the plight of racially oppressed people vis-à-vis physicians and medicine. We were intentional in taking into consideration those small acts of resistance that allowed our ancestors to continue to inspire our loved ones to survive hostile social worlds, and despite all the violence, find some form of respite (Camp; Lussana; Adams; Dusselier; Knaut). To do this, our workshop engaged participants to discuss aspects of the historical record where oppressed people used the body as a site of resistance. In addition, we also centered on exploring oral histories to discuss knowledge on healing by oppressed people.

Just Yesterday approach with the Counterspaces+Art Model

We were attracted by the Weisman’s Just Yesterday outdoor approach of using raw, in-your-face posters featuring well-known cultural moments in U.S. recent history alongside icons and famous historical figures to “talk back” and complicate the silence and collective White ignorance masquerading as innocence around the oppression and social dispossession of marginalized communities. This juxtaposition of images and facts reminded us of methods used in the medical humanities that put the learner in a state of cognitive disequilibrium and discomfort. Kumagai and Wear (Kumagai and Wear) describe this particular method as “making strange,” by placing the learner in a state of emotional imbalance “when encountering a person, an experience, or a perspective which is unfamiliar” (Kumagai and Wear 974) to them. We asked the participants to focus on how their work can place the viewer in a state of discomfort and curiosity, to compel them to explore issues and instances of U.S. historical racialized abuses they may not have reflected upon in the past.

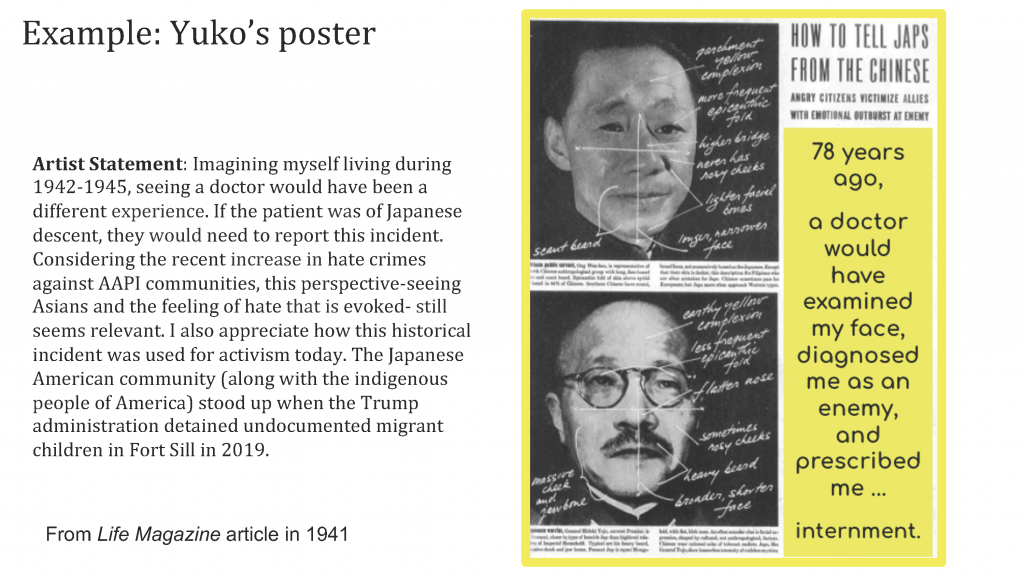

Yuko and I created sample posters to show how discomfort could shed light on practices of the now and how the past has shaped them but also how dominant (yes, I mean White) social groups and communities tend to ignore the recent racialized past. In one of the sample posters, we discussed how Yuko speaks to the recent acts of U.S. imperialism on Japanese-Americans via the use of internment camps and the role of medicine on the othering of a whole community due to ethnicity and race.

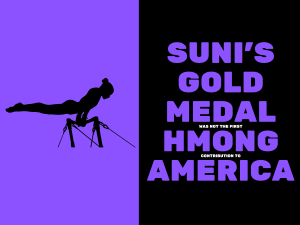

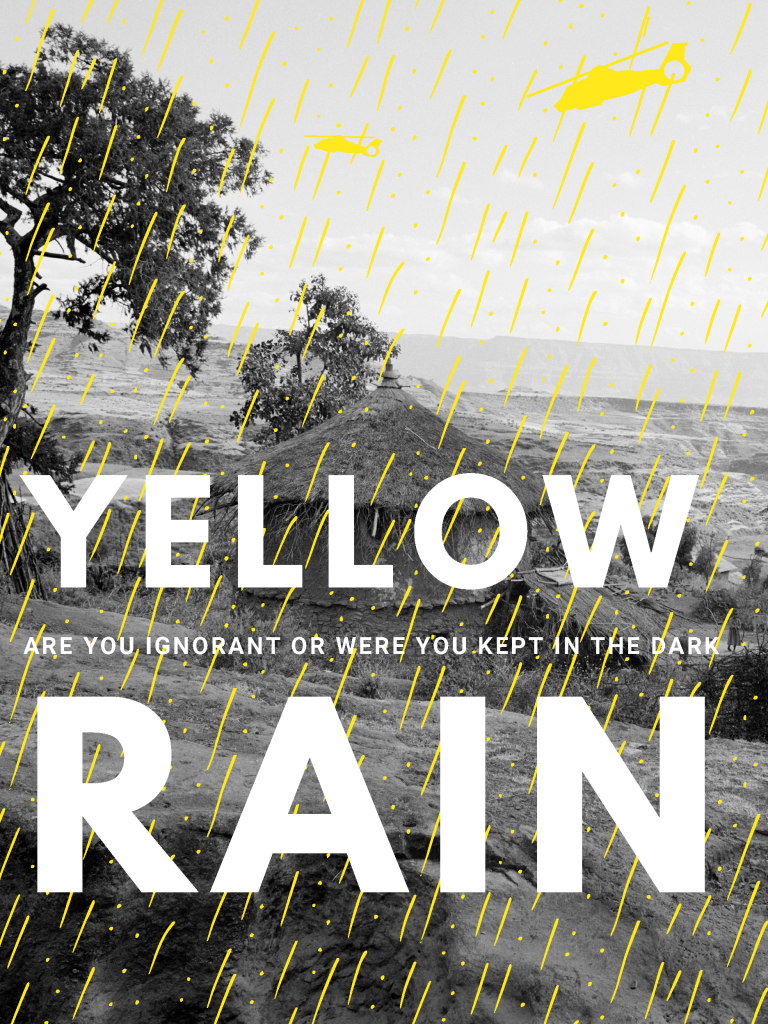

Our participants then collaborated to think of practices of oppression in the near present or recent past, or incidents of racialized violence that might be featured in their poster to emotionally shake their viewers into a state of discomfort. For example, those who might encounter the poster created by Kao, a third-year Health Sciences Hmong student at UMR, would be shocked and yet curious about the melding of recent well-known practice of U.S. imperialism (a war of recolonization of a country like Vietnam), the not-so-known role and place of Hmong people at this time in history, and a message that “talks back,” (hooks) bravely, plainly, yet powerfully, to a viewer who experienced a partial retelling of U.S. history. Additionally, the place and space where a poster like this may reside asks the (possibly White and Minnesotan) viewer whether they “[a]re ... ignorant… or ... kept in the dark?” about the history of a very visible (yet culturally invisibilized) non-White minoritized community in Minnesota. As a health sciences student, Kao also brings to the center the role of war in using science as a way to destroy the vitality and future of a group of people. (Agent Orange was, after all, an herbicide turned biomedical weapon used by the U.S. to bring a country to heel.)

Politics of Discomfort and the Role of Museums

What happens when we excavate the subaltern knowledge and practices of our ancestors and communities and make them central sources of inspiration and part of our professional identities? As neoliberalized spaces, including the very university system that pays our salary, continue to promote a culture and a set of practices that disallow connections and transformative praxes, we aim to continue nurturing counterspaces via art and anti-racist pedagogies. These spaces, places, and practices may be the few left where BIPOC in socio-professional contexts could create products (whether intellectual, aesthetic, or emotional) that recenter those ways of knowing that the neoliberalist academy tends to co-opt, exploit, or de-politicize. As we continue offering these workshops, the Weisman Art Museum and other partners have begun tapping into the social justice potential of providing dedicated spaces, resources, and energies that allow BIPOC in Minnesota to explore the transformative power of art and anti-racism praxis and their communities’ role in a moment defined by a collective response for social justice and accountability since the murder of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. This blog post, alongside Yuko’s, is our invitation for others to listen and act, even if doing so means experiencing discomfort. It is within these uncomfortable conversations that we can begin dreaming and building more just practices and futures, in medicine and beyond.

RESOURCES

Adams, E. Charles. “Passive Resistance: Hopi Responses to Spanish Contact and Conquest.” European Intruders and Changes in Behaviour and Customs in Africa, America and Asia before 1800, Routledge, 2017, pp. 41–55.

Camp, Stephanie MH. “‘I Could Not Stay There’: Enslaved Women, Truancy and the Geography of Everyday Forms of Resistance in the Antebellum Plantation South.” Slavery and Abolition, vol. 23, no. 3, Taylor & Francis, 2002, pp. 1–20.

Case, Andrew D., and Carla D. Hunter. “Counterspaces: A Unit of Analysis for Understanding the Role of Settings in Marginalized Individuals’ Adaptive Responses to Oppression.” American Journal of Community Psychology, vol. 50, no. 1–2, Springer, 2012, pp. 257–70.

Dusselier, Jane. “Gendering Resistance and Remaking Place: Artin Japanese American Concentration Camps.” Peace & Change, vol. 30, no. 2, Wiley Online Library, 2005, pp. 171–204.

Grier‐Reed, Tabitha L. “The African American Student Network: Creating Sanctuaries and Counterspaces for Coping with Racial Microaggressions in Higher Education Settings.” The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, vol. 49, no. 2, 2010, pp. 181–88.

hooks, bell. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. South End Press, 1989.

Knaut, Andrew L. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680: Conquest and Resistance in Seventeenth-Century New Mexico. University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

Kumagai, Arno K., and Delese Wear. “‘Making Strange’: A Role for the Humanities in Medical Education.” Academic Medicine, vol. 89, no. 7, 2014.

Lussana, Sergio. “‘No Band of Brothers Could Be More Loving’: Enslaved Male Homosociality, Friendship, and Resistance in the Antebellum American South.” Journal of Social History, vol. 46, no. 4, Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 872–95.

Solorzano, Daniel, et al. “Critical Race Theory, Racial Microaggressions, and Campus Racial Climate: The Experiences of African American College Students.” The Journal of Negro Education, vol. 69, no. 1/2, Journal of Negro Education, 2000, pp. 60–73. JSTOR.

Washington, Harriet A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Doubleday Books, 2006.

Yosso, Tara. Critical Race Counterstories along the Chicana/Chicano Educational Pipeline. Routledge, 2013.

---. “Critical Race Theory, Racial Microaggressions, and Campus Racial Climate for Latina/o Undergraduates.” Harvard Educational Review, vol. 79, no. 4, Jan. 2010, pp. 659–91.

Yosso, Tara, and Corina Lopez. “Counterspaces in a Hostile Place.” Culture Centers in Higher Education: Perspectives on Identity, Theory, and Practice, Stylus Sterling, VA, 2010, pp. 83–104.

Angie Mejia, Ph.D.

Angie Mejia, Ph.D., is Assistant Professor and Civic Engagement Scholar at the Center for Learning Innovation at the University of Minnesota Rochester. As a sociologist and educator forever in a state of nepantla, she encourages others to serve as bridges by introducing them to Black, Feminist of Color, and transnational feminist theories and methods. Her research uses intersectional analyses, critical participatory methods, and arts-based research collaborations to study emotional health inequities in historically marginalized communities of color. Her scholarly work has appeared in several academic journals, including Action Research, Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research (SPUR), Anthropologica, and Cultural Studies <-> Critical Methodologies.

Counterspaces workshop

The Counterspaces workshop is dedicated to providing a safe and welcoming space for members who self-identify as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC, including those claiming multi-racial identities) to reflect, express, and share their own stories through creative writing and poster making. This two-hour workshop was led by Dr. Angie Mejia (sociologist) and Yuko Taniguchi (poet).

This workshop drew inspiration from Just Yesterday, an outdoor installation which was on view at Weisman Art Museum through Oct. 1, 2021. Workshop participants were invited to offer reflection and contemplation of systematic injustice through bold and colorful posters that contain iconic pop culture references, and Counterspaces at Rochester Art Center, a collective healing project for Rochester community members who have been impacted by the existing and increasing acts of racialized violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC).