FEATURED ESSAY

Upon entering Vesna Kittelson’s North Loop Minneapolis studio, you notice that her space is populated with the faces of Young Americans. The painted portraits, slightly larger than life, are unfettered by frames and hung directly on the wall, most of them at eye level or just above. You can’t help but meet their gazes; most are looking straight on. Their features and apparel reflect a wide range of backgrounds, but they are, unmistakably, individuals, not cultural proxies. They are beautiful, in the way young people always are: each face unmarked by time and experience, glamorous in their youth.

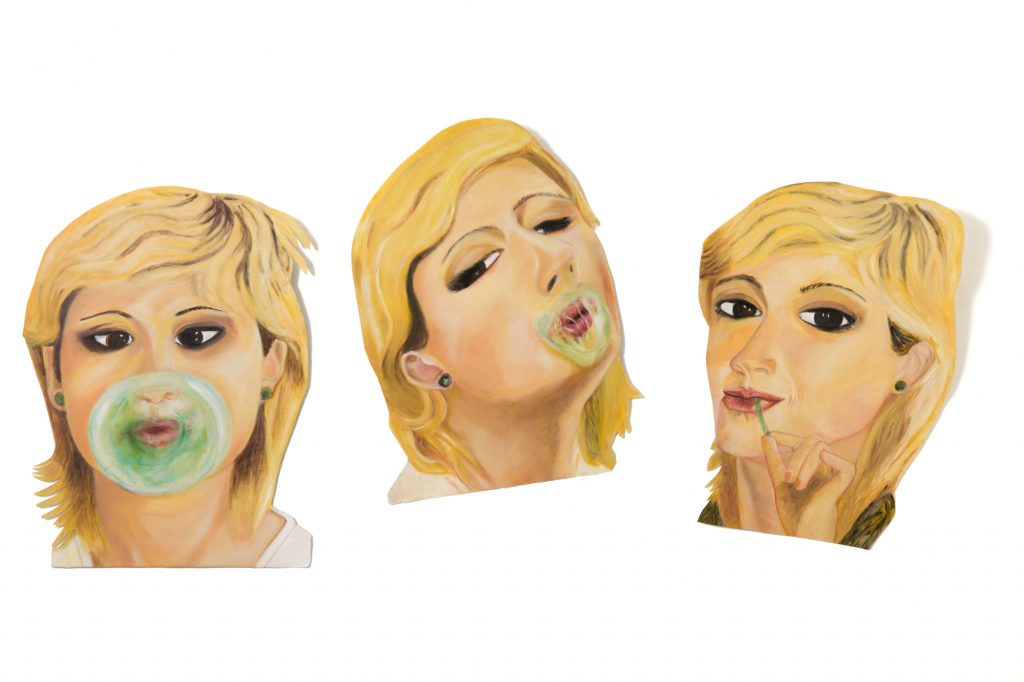

Scan the room, and Lulu arrests your attention. The portrait’s subject is an African American young woman, a Somali immigrant. Her expression is unsmiling, forthright and serious, but not unfriendly. By comparison, her brother’s expression in Harvey seems boyishly open. With his red and blue hoodie and white T-shirt, thick gold-chain necklace, and diamond stud earrings, he’s got that cool look of middle-class American teens everywhere. Nearby, Jack, a young Croatian man, looks out coolly as well, his gaze shuttered behind dark sunglasses. Adam, an Israeli American, faces the room sidelong, peering into the middle distance with his wild curls pulled back in a messy ponytail. Areca looks into your eyes with a glimmer of challenge in her own, no nonsense and unapologetically sober. The mood shifts dramatically with Christine, who is caught in a moment of laughter—tongue captured between her teeth, eyes squinting shut and her grin wide; the expression on her face is as vivid as her pink-tipped hair. Look around, and there are many more: Isra, with her fringed head scarf and smiling eyes; Kara, in triptych, blowing bubbles with her gum, eyes crossed. Mandy is luminous, but her expression is shy; in contrast, William’s soulful, downturned eyes are candid as they meet your own. Maya chews on her lower lip, as if nervous to hold your gaze, her hair barely restrained by her black-checkered headband. Seen together, the portraits implicate you in their gathering, invoking a sense of community in the space, as if you are meeting strangers at a party.

A child of mid-twentieth century Yugoslavia, Kittelson was raised in Communist territory, but she was weaned on American movies, music, and fashion. Surrounded by the political and cultural turmoil of the Soviet Union, for young Vesna the America of her dreams was more than a place. It was an aspiration—an ideal as expansive and full of promise as a summer’s night sky filled with stars to wish on. Her parents were progressive for their time and place and pro-American in their sentiments. In particular, Kittelson recalls, they revered the U.S. Constitution and its Bill of Rights. “Self-determination was unknown in a poor Communist home,” she says. “The idea of entering the middle class through achievement and hard work—the opportunity of America—is remarkable.” And through the many faces of her Young Americans portraits (painted from 2005 to 2013), it is this American dream that Kittelson aims to capture. Geography doesn’t matter when it comes to such things, she says. America is an idea, not a place. As one of her subjects, the young Croatian, Jack, said: “We are all Americans on the inside.”

The Young Americans portraits are all rendered in oil on archival paper, fortified with silk backing for structure. Kittelson is a deft colorist—it’s her technical and academic specialty. Her hues are lush, velvet in their saturation. Her skin tones are nuanced and radiant, as if lit from within. When asked about her atypical cut-out installation of the portraits, she explains: “Framing is a wholly Western convention having to do with property, delineating borders and boundaries. It’s a nineteenth-century idea that doesn’t resonate with the realities of contemporary life.” If we want to learn how to come together, how to hold on to the promise of a thriving, pluralistic society, she says, we have to be prepared to deconstruct outdated mores of ownership and exclusivity. In fact, the act of putting scissors to paper completes the portrait: the raw edge of the cut is the defining line that puts the portrait in direct relation to the viewer. Excised in this way, the faces make the wall a space in the work, a canvas of sorts. Her scissors becomes an existential device, defining new parameters to the world.

Kittelson’s formative years were spent in Split, Croatia, one of the oldest continuously occupied cities remaining from the Roman Empire. The ruins of Emperor Diocletian’s fourth-century palace serve as the site of Split’s bustling “old town” city center today. As a child, Kittelson was fascinated by the commonplace remnants of Split’s deep past—Egyptian granite sphinxes, various and sundry bits of statuary. She grew up surrounded by an architectural palimpsest of Roman, medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, and Soviet design and influence. “Given my childhood in such a place,” she says, “I’ve always been comfortable with the fragments of history. A bust feels natural to my eye. I’m interested in the simultaneity of time and tradition—history, present, future, all happening at once, fragmented on one end and united on another.”

She is an avid student of European art history. She calls out the influence of early twentieth-century German painter Max Beckmann on her sensibility: “He was a painter who was interested in civilians, not armies—ordinary people victimized by political structures acting upon them.” She continues her litany of favorites: “Velázquez, Goya, Picasso—we can’t dismiss Picasso! He did busts and fragments, like me, and he also abandoned traditional art techniques.” Early on, she says, these artists were central to her own creative growth. “But I’ve since invented my own parameters for practice, rather than being reliant on other artists’ conventions. Mine isn’t a practice rooted in preconceptions or inherited techniques; the rules I set for myself were all discovered in the making.” She’s a self-proclaimed “baroque minimalist—over the top and cut back.”

The Young Americans series began with a question. Kittelson pondered: What is the most democratic thing about America? “I’m not talking about legal protections and abstract civil liberties,” she explains. “I’m talking about the evidence of democracy as demonstrated in daily life—democracy in action.” A studio art instructor for many years at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD), Kittelson found her question’s answer in the stories and faces of the young people she taught on campus, some of them immigrants like her. “I’m astounded by the promise of these young men and women. They have such flexibility and adaptability. They expect the best of themselves and their peers, and see democracy as a plastic medium. I do, too.” Young people don’t take for granted their creative power to shape democracy, she says. It’s not abstract; it’s not merely conceptual. They practice it.

Kittelson’s Young Americans portraits are rooted in conversations. She needs to know her subjects’ stories, their point of view on the world, before she can paint them. “My first consideration is that emotional connection, capturing something of the distinctive intelligence of the person I’ve chosen as my subject.” The specifics of capturing their visage come next. And in the process of creating that likeness, the painterly gesture of putting brush to color and paper, she finds “the resonance that will make the image spark.” She uses a reference photograph on occasion, but it’s much smaller than the finished portrait; she always takes those photographs herself. The photography is, in a sense, her first portrait; she describes the photographs as her “preliminary drawings.”

To understand Kittelson’s Young Americans project, one must first consider the artist’s own American story. At twenty-two, as a new lawyer just graduated from law school in her native Croatia, Kittelson received a grant to pursue a deeper study of English at Newnham College for women at Cambridge University in the UK. The child of a seaside community, where most worked, in some capacity, for the shipyards, she had studied maritime law in her homeland and needed to improve her English language skills to be able to draft and negotiate international contracts. At Cambridge she met another international student, a scientist, who would become her husband, David, a Norwegian American from Pelican Rapids, Minnesota.

When he brought her back to America to begin their lives together, Kittelson’s trajectory changed. Up to that point, she had imagined channeling her lifelong love of art into collecting, while following a more practical, expected professional career in law. As a brand new American, she dared to dream of pursuing a different path, a life making art herself. Shortly after establishing a home in the United States, she returned to college for her undergraduate and master’s degrees in studio art and design at the University of Minnesota. In the years that followed, she raised her son and cultivated her art practice. As her son grew up and her art began garnering more notice, she deepened her roots in the Twin Cities art community: she taught painting as an instructor at MCAD from 1995 to 2009; was a founding member of the Traffic Zone Center for Visual Arts cooperative in Minneapolis; and was a member of the Women’s Art Registry of Minnesota (WARM) and Form + Content co-op gallery, among other activities and organizations.

________________________

Kittelson's art is irrevocably shaded by the in-between nature of her life as a hyphenated American, the back-and-forth of her identity and cultural frameworks. To her, these young Americans embody the ideal of American promise and freedom, in practice and made flesh.

________________________

Kittelson’s practice is mercurial—unbound to a fixed medium, style, or sensibility. For her, content drives form; ideas inform the structure and composition of her work, from sculpture to artist books, collage, and painting. She’s a visceral artist, formally educated and skilled but unconcerned with demonstrations of technical prowess. “I don’t care so much about technique,” she says. “I’m drawn to open-ended questions: what impacts us? That’s what drives me.” The lens through which she makes and views her art is irrevocably shaded by the in-between nature of her life as a hyphenated American, the back-and-forth of her identity and cultural frameworks. “I am both a participant and an observer here,” she says. And for her Young Americans project, Kittelson was drawn to capturing others in her community whose experiences resonated, in some way, with her own.

As an instructor at MCAD, she watched young people from a variety of cultural communities and backgrounds learn how to be together and live side by side, despite their differences. To her, these young Americans embodied the very best of democracy in action, the ideal of American promise and freedom in practice and made flesh. “I got to know such intelligent, thoughtful youth when I was teaching. I wanted to paint them, to capture that intelligence and spirit I saw in them in their portraits.”

It all began with Areca, an African American woman who was studying at MCAD for a semester and taking one of Kittelson’s classes in advanced painting. She was biding her time in Minnesota waiting for her Norwegian American fiancé, an architect, to finish a project in Marine on St. Croix, a small town near the Twin Cities. Kittelson and Areca were talking one day, and Areca asked what it was like to grow up in Communism. Kittelson offered her a deal: “I’ll tell you about that, if you’ll tell me what it’s like to be a Black person in America.” Areca described her experience as one of very few African Americans in a well-heeled, small Minnesota town. She told Kittelson about her litmus test for finding allies there: shortly after she and her fiancé arrived in town, Areca baked cakes for her neighbors, and she took a cake to each house, one by one, to see who would answer the door and turn her away and who would greet her warmly. Kittelson told her about life under Communism and related her own experiences straddling European and American life and identities.

After they had shared stories, Kittelson asked to paint her portrait: “She agreed to sit for me, on the condition that I didn’t ask her to smile.” Areca had worked as a model and said she always felt self-conscious and phony when made to smile for pictures. Kittelson painted her wearing an expression Areca found most natural—no fake smiles, nothing put-on.

Kittelson’s subsequent portraits followed suit. She is emphatic about the creative purpose of her deeply personal approach. Her Young Americans are subjects in every way, not symbols, objects, or specimens. “My paintings need to capture these young people as breathing, thinking, feeling persons,” she says. “I’ll cut everything else away in order to get that.”

“Young Americans” was originally published in Synthesis: Lost and Found in America. The Art of Vesna Kittelson (Afton Press, 2020). Copyright 2020 Susannah Schouweiler. Copies of the book, signed by the artist, are on sale now at the WAM Shop: pick up a copy in person, or order online for curbside pick-up, or to have it shipped to your door.

ON VIEW: Selections from Kittelson's Young American series are on view in a featured installation at the Weisman through January 3, 2021.

Essay by Susannah Schouweiler, director of communications and marketing for Weisman Art Museum. In addition to her role at WAM, she is an occasional writer and editor whose work appears in local and national publications, including Hyperallergic, American Craft, Public Art Review, Rain Taxi Review of Books, Ruminator magazine, MinnPost, City Pages, and others.