FEATURED ESSAY

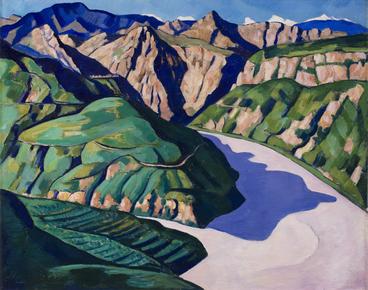

Luminous swaths of green, yellow, and purple spread and seep through the surface of the canvas, capturing the attention of gallery visitors. The paint still looks alive with movement nearly fifty years after its deployment. The brilliant colors captivate viewers immediately, but after observing for a minute or two, one may be inclined to ask, “What is it?” Discerning the subject of Helen Frankenthaler’s 1973 painting, Cravat, is a challenging, perhaps even futile, task. The limited research done on this painting compared to Frankenthaler’s other works further obscures a definite interpretation of its content. However, the significance of Cravat arguably lies less in its subject matter and more in the methods behind its creation and in the history of the work itself. To understand both aspects, one must become acquainted first with the artist and then with the painting in question.

Born in Manhattan in 1928, Frankenthaler was the youngest of three daughters to her mother and father, a New York State Supreme Court Judge. Growing up on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, Frankenthaler experienced economic privilege as well as support from her family from an early age to pursue a career as an artist. Frankenthaler graduated from the Dalton School, New York in 1945 and from Bennington College in 1949. She studied under esteemed modernists Rufino Tamayo, Paul Feeley, and Hans Hoffman among others during her time as a student. Despite studying with successful painters and learning first-hand about expressionism, abstraction, surrealism, and cubism, Frankenthaler claimed that living in New York during the 1950s was her greatest source of education.

As the birthplace and international hub of Abstract Expressionism after WWII, New York was constantly pulsing with the latest innovations in Modernism. Frankenthaler’s own artistic style emerged from her engagement with Abstract Expressionists of the previous generation, such as Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, and Jackson Pollock. Building on Pollock’s thickly layered paint and stained canvases, Frankenthaler experimented with oil paints thinned with turpentine—a watery concoction—which she poured directly onto an unprimed canvas on the floor. This practice allowed the paint to soak and spread through the canvas. The stained fibers of the canvas created a completely flat, but no less vibrant, abstract painting. Her aptly named “soak-stain” method became a great success, catapulting Frankenthaler into the limelight as an innovative and talented color field painter. Her first group exhibition opened in 1950, just one year after she graduated from Bennington College. The following year, she had her first solo exhibition at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery. Her first retrospective followed in 1960 when she was just 31, unusually young for a painter at the time to receive such recognition from prestigious institutions.

In her early career, Frankenthaler befriended Grace Hartigan, a fellow second-generation Abstract Expressionist based in New York. Frankenthaler and Hartigan shared an admiration of the Impressionist painter, Berthe Morisot, who they looked up to as a pioneer among modern women painters. They bonded not only over their love and admiration of her work, but also over the sorrow they felt for Morisot knowing that her freedoms in the late-19th century were a fraction of their own in the 1950s and 1960s. Frankenthaler and Hartigan read and discussed Morisot’s personal writings which expressed deep unhappiness towards her life as a woman and the despair of knowing she could not succeed to the extent of the male Impressionists around her despite her talent. Taking Morisot’s tragedy as inspiration, Frankenthaler and Hartigan forged their own artistic styles and methods without allowing themselves to be downplayed as “women artists” or feminine painters. They aimed to create art without attaching their identities as women to their work, insisting that their paintings could speak for themselves. While Frankenthaler’s earliest groundbreaking works predate the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s by nearly two decades, she has been retroactively described as a feminist pathfinder by those who recognize her efforts not just to create her own space in a stifling field, but also to emerge as a highly-respected artist whose contributions inspired many painters after her. Frankenthaler’s staggering number of solo and group exhibitions, awards, and retrospectives speak to her success as “more than a woman artist” and validate her as a great artist in her own right.

By the 1960s, now a decade into her established career, Frankenthaler exchanged turpentine-thinned oil paint for watered-down acrylic, which she found more vibrant and intense. While she continued to make color field paintings using her soak-stain method throughout her career, Frankenthaler constantly modified her approach to reflect her personal experiences and her passion to create original, spontaneous pictures. In Cravat, for example, Frankenthaler includes horizontal lines in the top and bottom thirds of the composition, an element absent in her earlier color field paintings. Frankenthaler included these hand-painted lines in several of her paintings from the early-1970s as a result of her travels to North Africa where she observed calligraphy and geometric designs on walls and mosques.

While the content of many paintings in the 1970s became harder to decipher, landscapes still featured prominently, though depictions of real locations became scarcer. Rather than a realistic representation, the vast majority of abstract landscape paintings in the 1970s offered a suggestion of nature using color and texture to allude to sky, land, and sea. In this way, artists created something to be meditated on rather than easily interpreted. Is Cravat this type of landscape? Does Frankenthaler use color and shape to suggest an expanse of sand, a grass-covered hill, and vibrant, purple clouds over a faintly visible sea? Whether or not Cravat is a landscape, Frankenthaler did verify that some of her paintings, like her famous 1952 painting, Mountains and Sea, were inspired by landscapes she witnessed during her travels or by views from her sea-side home in Connecticut where she spent her later years.

But what about the title? While ‘cravat’ typically refers to a necktie tucked into a shirt collar, the meaning is unclear in Frankenthaler’s painting. Frankenthaler often allowed images and allusions to form organically in her paintings, claiming that she saw images in the final work in spite of any intention to create such images. While Frankenthaler possibly saw a likeness to a necktie once she finished Cravat, perhaps in the green formation in the center of the work, there is no definitive evidence to confirm such a claim.

Though she refrained from working in series, several of her paintings from the early 1970s bare a similar color palette and overall design. For example, Nature Abhors a Vacuum, also painted in 1973, contains similar hues of green and yellow as Cravat. Horizontal lines can be seen in both works and both titles seem to oppose any direct connection to a definable subject. Nature Abhors a Vacuum is a widely recognized work by Frankenthaler. Since the 1970s, it has been well documented and widely exhibited. Though the two paintings would seem to be strikingly similar in some respects, Cravat’s recognition pales in comparison to that of Nature Abhors A Vacuum. This may stem from Cravat’s history of ownership.

After Frankenthaler painted Cravat in June of 1973, Andre Emmerich, a reputable art dealer, gallerist, and collector in New York, obtained the work to become Cravat’s first documented owner. Frankenthaler and Emmerich had a close professional relationship in which he served as Frankenthaler’s art dealer and her repeated exhibitor for many years. Art collector Gilbert H. Kinney became the next owner of the work, presumably purchasing Frankenthaler’s painting from Emmerich in the mid-1970s. Kinney later auctioned Cravat through Christie’s Auction House in New York in 1989 where it was purchased by Arnold and Sylvia Goldman for their private collection. The painting was involved in one traveling exhibition during Kinney’s ownership, though extremely few published texts on Frankenthaler mention Cravat, let alone delve into descriptions or interpretations of its content. Due to its movement solely between private collections, those who did not frequent Emmerich’s gallery or visit one of the six museums to display Cravat between 1978 and 1980 likely never saw the work in person.

Arnold and Sylvia Goldman, a Minnesotan couple, owned the painting for 25 years before they generously donated their collection of 62 modern artworks, including Cravat, to the Weisman Art Museum in 2014. Since entering WAM’s collection, Cravat has been featured in three exhibitions, two of which exclusively highlighted the works gifted by the Goldman family. Cravat was also present for the wedding of Arnold and Sylvia Goldman’s daughter, which was held at WAM the year following her parents’ donation. Today, works like Cravat are labeled with the acknowledgement “Gift of the Arnold and Sylvia Goldman family” to recognize their contribution.

Finally possessed by a public institution and continuously on display since 2018, Cravat is now available for the first time in 40 years not only to the public, but also to art historians who could further engage with Frankenthaler’s work through this essentially unstudied painting. Despite the opportunity to view and study Cravat, however, discerning the subject of the painting or the relationship between its title and content may still be impossible. The best answer to the question, “what is it?” may come directly from Frankenthaler: “What concerns me when I work, is not whether the picture is a landscape, or whether it's pastoral, or whether somebody will see a sunset in it. What concerns me is - did I make a beautiful picture?” Following Frankenthaler’s lead, viewers can stop struggling to find imagery or hidden messages in Cravat and simply enjoy Frankenthaler’s beautiful picture. Currently on view in the Babe and Julius Davis Gallery following its long journey from collection to collection, Cravat eagerly awaits thoughtful meditation and admiration of its vibrancy and beauty upon readers’ next visit to

WAM.

Image:Helen Frankenthaler, Cravat, 1973, acrylic on canvas. Gift of the Arnold and Sylvia Goldman family.