In 1991, I didn’t anticipate the reactions of my art school peers when I told them I had been working as an “exotic dancer” for the past year and a half. Of course I knew that it was a somewhat transgressive job and might bring me some notoriety, but I hadn’t expected to be pitied, seen as exploited, or accused of false consciousness. And their image of what dancers were like didn’t match the women with whom I had worked.

I can’t say that I was raised a feminist, but I was certainly raised with a pop cultural feminist sensibility. When confronted with the attitudes of my classmates, I began reading feminist theory in earnest, in an effort to find writers who reflected my experiences with gender and sexuality. Authors like Susie Bright and Pat Califa, and magazines like On Our Backs, provided arguments with which to counter my classmates. They expanded my own perspective, introducing me to the concept of sex work, and challenged my own “whorephobia". This writing often focused on the empowering aspect of taking control of one’s own sexuality and sexual expression, positing consensual sex work as one choice among many. It felt validating and true to my experience, though it didn’t always address all aspects of it.

Almost 30 years later, the argument of exploitation versus empowerment is still raging in the mainstream. Sex worker exclusionary radical feminists and liberal feminists like Gloria Steinem still deny the agency of women who choose sex work, promoting policies and regulations that increase harm for both consensual workers and trafficking victims. Erotic dancers have more visibility than in the past, but are often reduced to stereotypes to further someone else’s agenda, rather than having an opportunity to speak for themselves. Fortunately, a new conversation is developing.

The winter of 2017-2018 brought us the New York Strippers’ Strike and the New Orleans Strippers’ Protests. The issues raised in these actions—unfair labor practices, racist hiring processes, over-policing of marginalized communities—are intersectional and go beyond the reductionist exploitation and empowerment narratives. These movements acknowledge the complex interplay of late capitalism, patriarchy, immigration policy, and white supremacy that affect the lives and working conditions of dancers. They link sex work with other forms of precarious labor to inform a larger discussion about the changing nature of work.

Mainstream media has covered these events and does increasingly give sex workers a platform to speak for themselves without sly winks or condescension from editors. Even staid TIME Magazine ran an article on how sex workers could inform discussions of consent in the #MeToo movement—discussions they are often left out of.

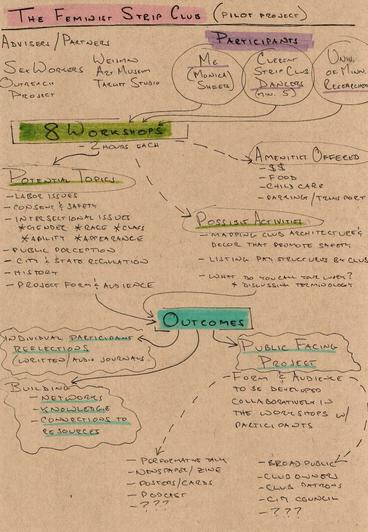

With the “Feminist Strip Club,” I want to help drive a cultural shift in conversations about sex work and the policies that regulate it. I have focused on erotic dancing because it is the industry I know best. I want to do this work in a considered way that centers the voices and experiences of erotic dancers, and that is why they are participants and co-creators in the project. Organizations such as Sex Workers Outreach Project are doing the hard work of meeting with legislators and organizing workers, but we also need spaces for reflection and for imagining what could be.

The question is not whether erotic dancing is empowering or exploitative, but rather how. What are the labor structures, business organizations, and cultural contexts that allow for diversity in gender and sexual expression, race and ethnicity, ability, body type, and more? How do we remove decisions about work from economic coercion? How do we remove stigma and reduce harm? In short, what does a feminist strip club look like?

Here are two articles I suggest for additional reading:

I’m a stripper, but that doesn’t stop me from being a feminist—MetroUK

Sex Is Not the Problem with Sex Work—Boston Review