FEATURED ESSAY

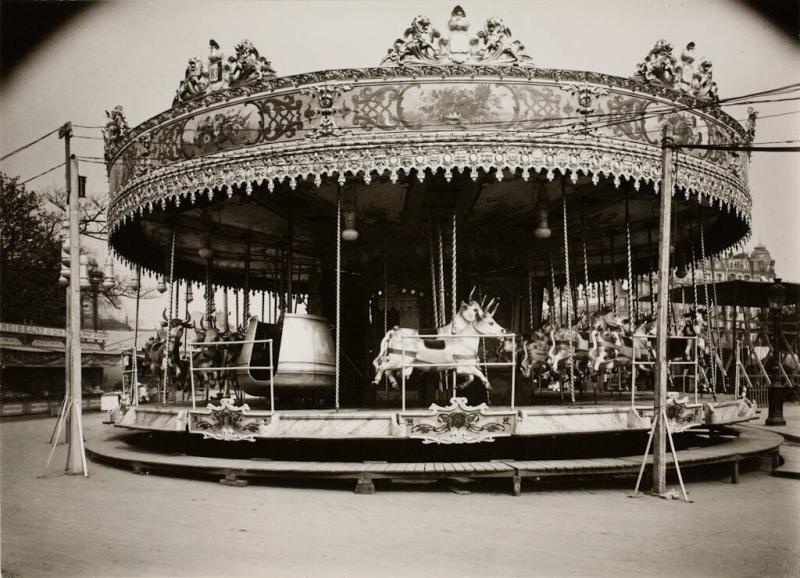

Eugène Atget’s documentary photographs, mostly taken in Paris during the early 1920s, offer haunting, uncanny city scenes bereft of human actors. Often beginning his work before dawn, Atget would carry a bulky (and increasingly obsolescent) bellows camera while strolling the streets, endeavoring to capture a city on the brink of dramatic urban transformation. These images are imbued with nostalgia and a sense of loss. The critic Walter Benjamin memorably compared Atget’s Parisian photographs to “the scene of a crime.” For Benjamin, the crime was that Paris would soon be unrecognizable, but Atget’s choice of subject in his gelatin silver print Carrousel (1923; Figure 1) also reveals a changing relationship between human and nonhuman animals with its own profound ethical implications.[1]

Like zoos, merry-go-rounds became popular in the late nineteenth century to cater to urban leisure classes in Europe and the United States. Both romanticize and infantilize animal life; both turn animal life into a spectacle for human consumption. Atget’s omission of humans in his photographs can then be read as an implicit critique of this increasingly exploitative relationship between humans and the natural world that was an inevitable consequence of urbanization, industrialization, and the rise of global capitalism.

The Zoo, Alienation and Complicity

This dramatically different relationship between human and nonhuman animals, as well as its visual and social traces, was expertly articulated in 1977 by the English critic John Berger in his polemic essay “Why Look At Animals?,” from which this exhibition takes its title. For Berger, it was no accident that the popularization of the zoo (and the carousel) coincided with the increasing absence of animals from everyday human life in the so-called “developed world.” Berger proposed that a certain nostalgia toward animals, manifest in their spectacularization and so intensely evoked by Atget’s photograph, was a phenomenon that accompanied industrialization and its attendant evolving labor practices. He writes that “the reduction of the animal . . . is part of the same process as that by which men have been reduced to isolated productive and consuming units.” In fact, the always-already disappointing act of a trip to the zoo, where animals are lethargic, depressed, and abused, becomes an act of “looking at something that has become absolutely marginal,” not unlike the alienated labor of workers on an assembly line. That same distancing enables human beings to ignore their own complicity in systems that cause harm to animals, by means of consuming them, wearing them, or encroaching on their natural habitats. Art about or involving nonhuman animals works to bridge these cognitive gaps.[3][2]

In resisting the common romanticization and infantilization in our popular imagery of animal life, the artists featured in Why Look at Animals? tell complicated and discordant stories about human/nonhuman relationships. Taking Berger’s question to task nearly fifty years after the essay’s initial publication, this exhibition investigates the Weisman Art Museum’s eclectic collection to ask how human actors have used (and misused) the figure of the animal to delineate the bounds of their own subjectivity and to discover what the all-too-human fixation with animals actually illuminates about our modern world and our place in it.

Us and Them

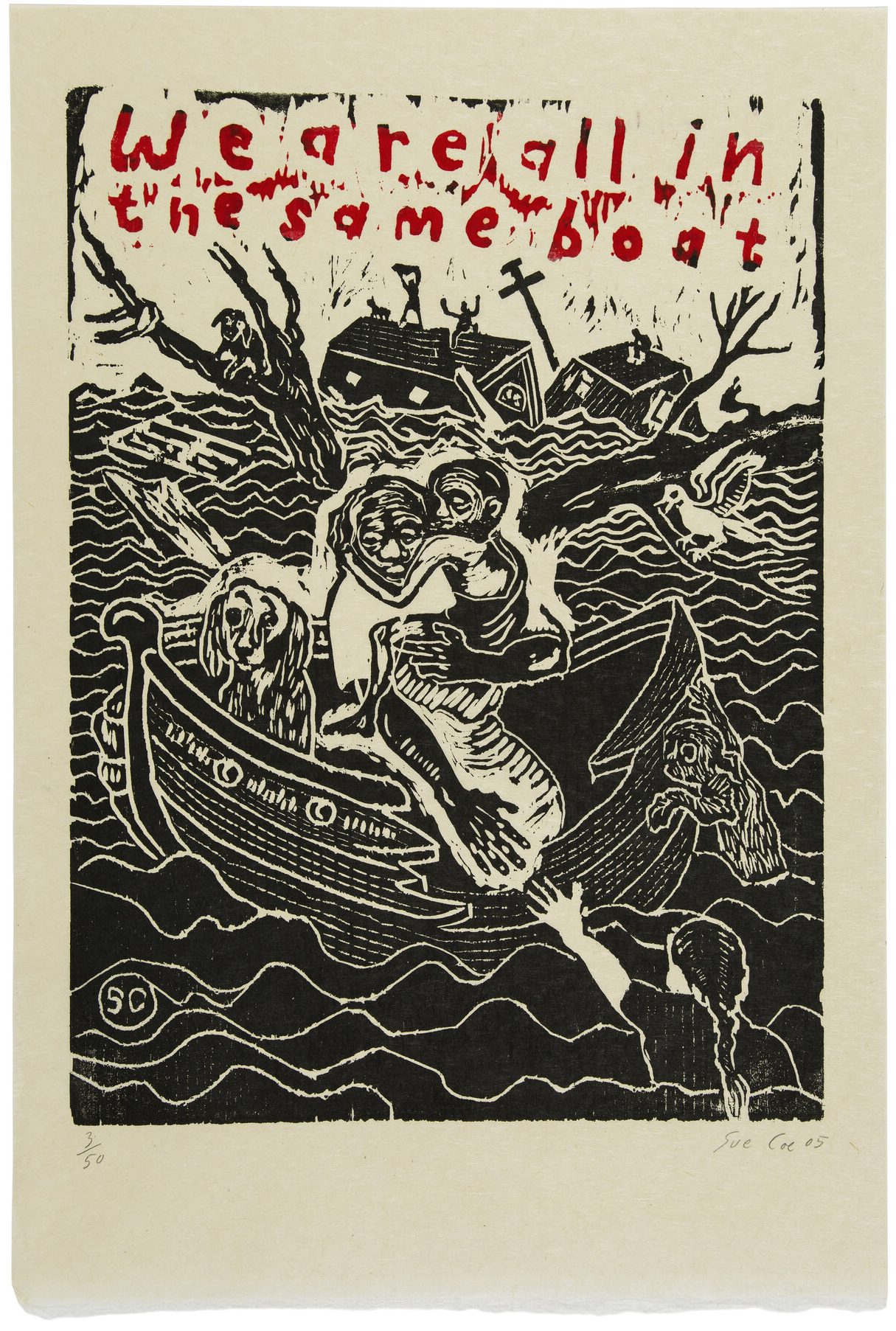

Some artists offer scenes of dynamic kinship and intimacy between humans and animals, thereby complicating ideas of both marginality and romantic nostalgia. Animal rights activist and printmaker Sue Coe accomplishes this in a single phrase: We are all in the same boat (2005; Figure 2). Her searing woodcut references the flooded streets and destroyed homes that characterized New Orleans’s predominantly Black Lower Ninth Ward after Hurricane Katrina. The central Black man holds a child in a boat they share with a dog, and he extends his hand to a white figure floating in the water while other animals also attempt to enter the boat. Chaos looms in the background, where humans and dogs wait fearfully on floating homes and trees. Coe suggests that although all species will inevitably reckon with suffering from the ecological devastation that is largely caused by the in/action of powerful humans, this harm and destruction will be disproportionately experienced by the marginalized. Coe’s concern echoes the feminist biologist Donna Haraway’s clarion call for “an ethics and a politics committed to the flourishing of significant otherness.” Sue Coe resists dominant narratives of individualism to instead demonstrate the interspecies and interracial solidarity that will be absolutely necessary for survival amid rising tides and temperatures.[4]

"The Savage Beast"

Other artists take up themes and tropes of animality toward unsettling and violent ends; they endeavor to chart the limits of what it means to be human. In his enigmatic duo of prints Dorco I and Dorco II (1990; Figures 3 & 4), Nicolas Africano presents animality as a mask, a costume that can be taken on and off to enable grotesque violence and separate oneself from both rationality and responsibility. In the first print, a wolf-like creature with a human body wounds an innocent lamb while retaining cool, calm, unaffected eyes. In the second, as more sheep surround and witness the violence, the figure removes his canine mask to reveal a wide-eyed human. Holding a dagger, he cradles the dying lamb as it bleeds and bleeds a rich red. Wearing the animal mask precipitates violence, and removing it enables empathy. Though trafficking in conceptions of animality that activists and scientists might challenge, Africano illuminates some of our culture’s most pervasive stereotypes about boundaries between human and nonhuman animals—namely, that humans are capable of rational thought and compassion, and animals are not.

Animals as Political Proxies

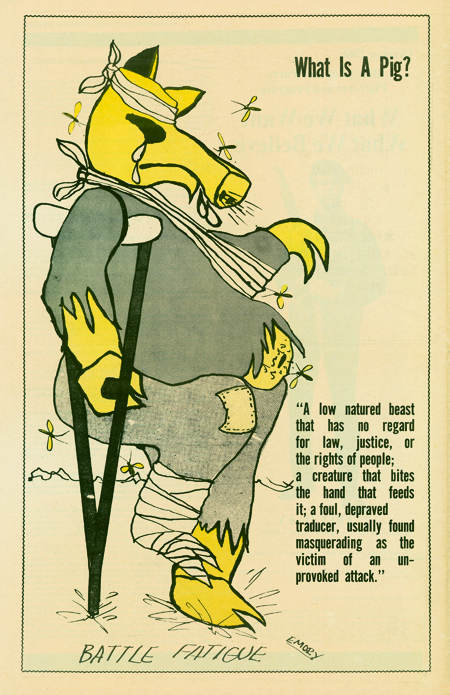

Though Berger was skeptical of anthropomorphic visual strategies, writing that “animals have become prisoners of a human/social situation into which they have been press-ganged,” other artists demonstrate the political efficacy of animal imagery as a means of depicting cruelty, as a tool for visualizing earth-shattering violence, and, importantly, as satire. Several issues of the Black Panther Party’s News Service join this exhibition on loan from the university library’s Givens Collection of African American Literature. Emory Douglas, the party’s Minister of Culture, drew on party vernacular to memorably anthropomorphize pigs as racist police officers and other agents of white supremacy. Through witty and incisive interplays of text and image, Douglas uses the figure of the animal to critique structures of power and to visualize paths toward an anticolonial, abolitionist, antifascist future. In Battle Fatigue (1969; Figure 5), Douglas debases a pig, rendering the animal pathetic and wounded, thereby visualizing the Black Panther Party’s militant and radical politics. Renewed conversations about police violence, accountability, and abolition since the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, of course, have made these illustrations all the more prescient.[5]

Through dissonant scenes of kinships, critiques, and encounters, the works featured in this exhibition provide visceral and timely complications to simple distinctions and hierarchies between human and animal. In much of Europe and in industrialized and settler-colonial nations, particularly the United States, the intertwined dogmas of “anthropocentrism” (or human-centered worldviews) and “speciesism” are dominant. First analyzed by philosopher Peter Singer, speciesism is the widespread and unexamined human prejudice against beings of other species. Why Look at Animals? takes up the call of the activists, artists, and scholars who have suggested that critically examining and reevaluating that bias might open the door to a more ethical, just, and ecologically feasible future on our shared planet Earth, and invites viewers to join us in that effort.[6]

Footnotes

Walter Benjamin, “Little History of Photography,” in Selected Writings: 1931–1934 (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 2005), 527.[1]

John Berger, “Why Look at Animals?” in About Looking (London: Writers and Readers, 1980), 13.[2]

Ibid., 26.[3]

Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003), 3.[4]

Berger, “Why Look at Animals?” 19.[5]

Peter Singer, “Animal Liberation,” in Animal Rights (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1973), 7–18.[6]

RELATED EXHIBITION

This essay is published in conjunction with the exhibition Why Look at Animals?, on view at the Weisman through February, 2024.

MEGHAN CLARE CONSIDINE

MEGHAN CLARE CONSIDINE is the curatorial assistant at MASS MoCA. She received her M.A. from the Williams College and Clark Art Institute Graduate Program in the History of Art in 2023. She was the 2020-2021 O’Brien Curatorial Fellow at Weisman Art Museum, at which time she worked with the Weisman’s curatorial team on various projects, including her work as guest curator for Why Look at Animals? Before her fellowship at WAM, she held positions at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and the Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University.