Although the Weisman Art Museum (WAM) is best-known for its works in American Modernism, there are several unique features of the permanent collection that make WAM a special treasure. One of my favorites is the Edward Reynolds Wright Collection of traditional Korean furniture, the largest collection outside of Asia.

Edward Reynolds Wright went to Seoul, South Korea, in 1967 to become the head of the Korean-American Educational (Fullbright) Commission. During the 11 years Wright lived in South Korea, he amassed a huge collection of Korean furniture, something that would not be possible to achieve today.

Several circumstances were crucial for this collection to form. With the Korean War ending in 1953, South Korea experienced a turbulent political atmosphere throughout the remainder of 1960s, driving many people to migrate to urban areas like Seoul. As urban spaces became more crowded in the aftermath of the war, original inhabitants were displaced and forced to sell their belongings in order to survive.

Over time, Wright, who was living Seoul, developed a keen eye for authenticity and worked to aggregate a collection of refined Korean furniture. As he traveled the world teaching, he kept his collection in a dingy San Francisco warehouse. Upon his death in 1988, his estate came to the University of Minnesota foundation and his furniture entered the collection of the Weisman Art Museum, as was his wish.

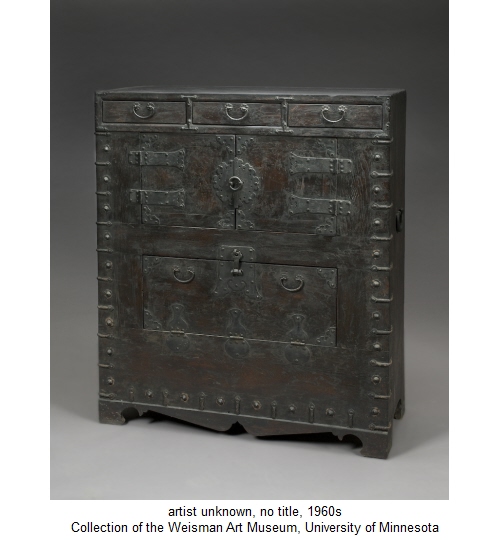

Korean furniture interests me because I find it fascinating to look at functional objects as a form of art. It is certain that the original owners of these works never intended for them to end up in a museum. The wardrobe chest in figure two relies on three different types of wood to provide the decorative element for the piece. An essential feature of authentic Korean furniture is appropriating and using old wood to create new objects. The creator here demonstrates considerable skill, as they seamlessly blended the types of wood to create an aesthetically pleasing work of art. The juxtaposition of the natural design of the grain of the persimmon wood alongside the stylistic white brass fittings makes the work truly striking. The form the object takes as a wardrobe allowed the owner to introduce an element of natural and artistic beauty into their home in a pragmatic manner.

From the homes of wealthy Koreans, to the streets of Seoul, to a seedy warehouse and finally to an art museum, the history of the Edward Reynolds Wright collection provides insight into systems of power and they way elements of diversity appear in our museums. Thoughts like these can spark conversations regarding the role of museums in preserving culture, and how taking objects out of context changes the way we view them.