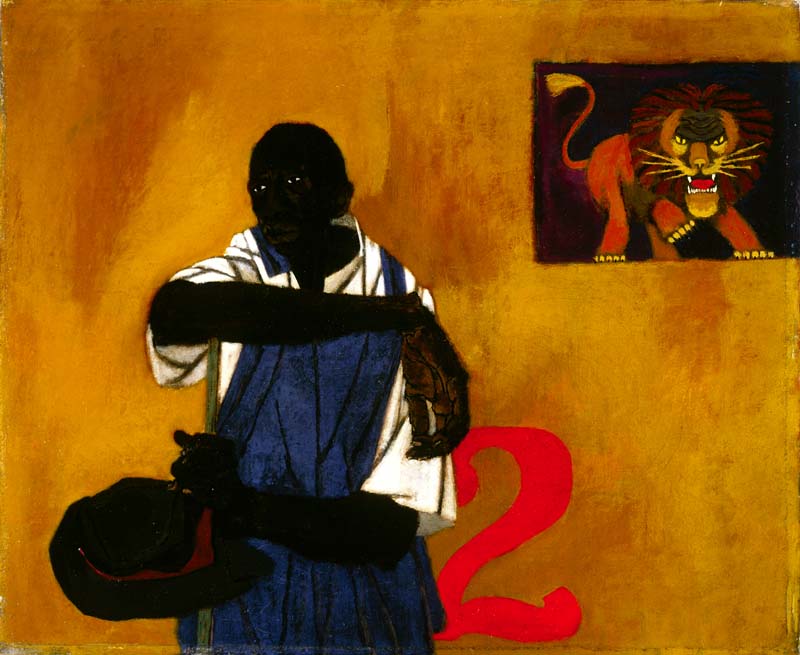

Nobody Around Here Calls Me Citizen, 1943

Oil on canvas, 141/2 x 17 in.

ABOUT THE ART

This painting combines a portrait of a black sharecropper with an image of a lion, perhaps taken from a circus poster, and the number “2.” A sharecropper is a tenant farmer who gives a share of his crops to the landowner to pay his rent. The contrast of the face and hands of the man with the stance and stare of the lion points to the strengths and hardships of both. The title and symbol of the number refer to the reality that citizenship and full human rights were denied to most African Americans in the South when this painting was made in 1943, some twenty years before the start of the massive civil rights movement in the United States. Gwathmey believed artists have a responsibility to social justice and that their work can help people think about important issues. “Artists have eyes … You go home. You see things that are almost forgotten. It’s always shocking.”

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Robert Gwathmey was a white artist born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1903. His mother supported his family by teaching. He worked his way through high school and art school in Philadelphia and became a painter and art teacher. He helped establish an artist’s union and became involved with politics and racial issues. When visiting the South, the harsh treatment black people received and the “acute blind spots of my boyhood friends and associates” shocked him. Every summer he returned, and in 1944 he lived on a tobacco farm working with black sharecroppers. Gwathmey’s own experiences led him to make paintings that would identify the racism he saw in America. He died in New York in 1988.

THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 and Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution freed African Americans from slavery and guaranteed voting rights, but traditions and local laws continued to deny many the full rights of American citizenship. Laws that segregated blacks from whites, called Jim Crow laws, persisted for 100 years. From bus seats and water fountains to schools and the ability to vote, African Americans were treated as second-class citizens. During World War II, as in previous U.S. wars, thousands of black soldiers joined the cause. Young soldiers asked to risk their lives to ensure democracy and justice in Europe returned to America to face injustice and be denied their democratic rights at home. The realization of this inequality was highlighted through photographs and artwork of the time and set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

BROWN VS. THE BOARD OF EDUCATION

The court case started in Topeka, Kansas, with a black girl who was not allowed to enroll in a white school near her house and was forced to make a long, dangerous walk across train tracks to the closest black school. In 1954 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in the case of Brown vs. the Board of Education that segregated public schools were unconstitutional and did not provide equal opportunity to students of color. This case marked the start of breaking down local Jim Crow laws through the authority and power of the federal government.

VOTING RIGHTS ACT

In 1965, after years of conflict, protests, voter registration drives, and after Alabama state police beat peaceful civil rights marchers in Selma, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into federal law. The Act ensures that no American citizen shall be denied the right to vote because of race or color. It allows for federal oversight of election practices in southern states and works to ensure a citizen’s rights stated in the Fifteenth Amendment.