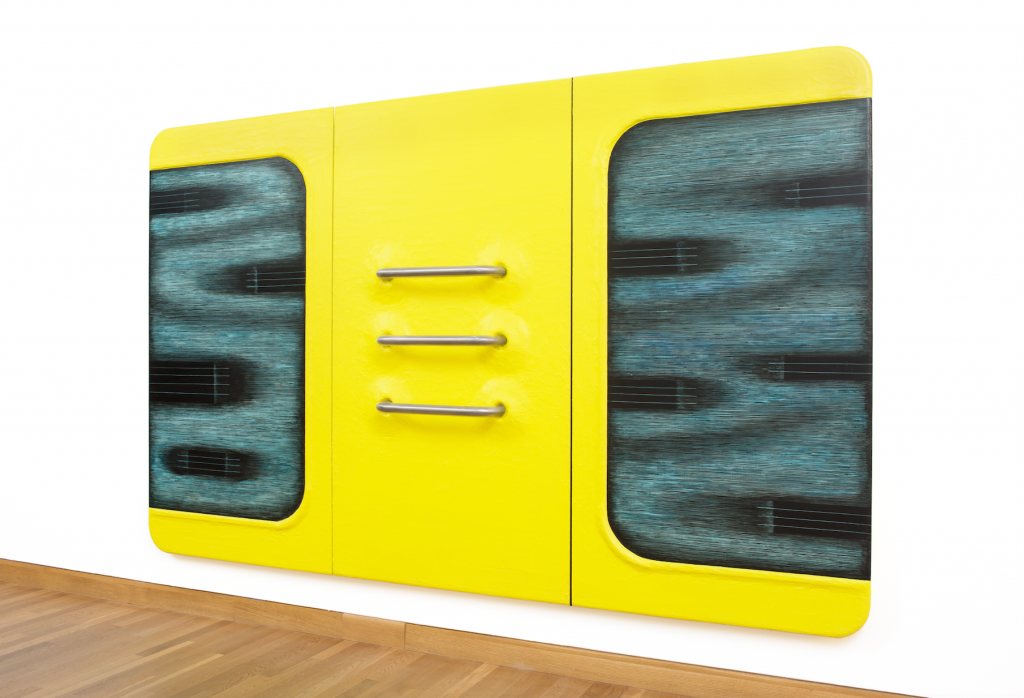

It is garish. It is massive. It, at times, protrudes. It seduces its viewer into examining every pulsating, changing inch of its black and yellow acrylics and it generates a subconscious, encompassing buzzing not unlike a pervasive television static.

No sound is literally produced. The canvas remains still.

Thus is the power of Tishan Hsu’s 1987 work Liquid Circuit. The title is just one of the riddles prompted by Hsu’s “sphinx-like creation”—a work that plays between moods of a cool, disaffected technological and a dynamic, gurgling biological. The biological moments glow with a pulsing nuclear power in an effect Hsu describes as an “ether.” The overbearing, almost noxious yellow is suggestive of a type of flesh (whether it originated from a futuristic, android, or alien being is difficult to say). Hsu’s exaggerated staples puncture the flesh, their entry points marked with keloid scars invoking the natural, communal, and eventual atrophy all organic bodies endure. Yet the luminescent flesh is stretched over the skeleton of Liquid Circuit’s twin monitors and given raidused corners, which equates the structure with insentient technology such as computers and television sets. The mysterious screens are certainly the originators of the enveloping white noise, as their static buzzes and paces up and down the canvas while searching for a signal. Vents appear between the gray and blue electromagnetic waves and though their presence hints at a Central Processing Unit, they do not reveal any underlying mechanics. On top of it all, the radioactive Liquid Circuit seems to breathe within the comfort of its own undulating atmosphere, again evoking Hsu’s “ether.”

It is a strange and contradictory biomorphic machine. Perhaps the answer to Liquid Circuit’s riddle lies in, as they always do, a calculating logic. It offers a treaty between the two moods, questioning whether such a difference needs to, or still, exists. Hsu argues for the reality of a merged identity between technology and biology. He demonstrates this balance through presenting a technological art with a distinct hand-craftedness. It is this presentation within Liquid Circuit that argues his locked technological system breathes and grows simultaneously with the viewer.

And why shouldn’t such a symbiotic relationship exist in the current era? In the same year of Liquid Circuit’s creation, the artist explained, “we make machines, then they make us.” After thirty years, Hsu’s insight is equally, if not more, relevant. In the twenty-first century, necessity emphasizes efficient and constant potential. In 2015, 92 percent of American adults owned cell phones and 73 percent owned personal computers. Information is no longer delivered in a linear format capped daily by the 10 p.m. news but is instead placed within an eternal blogroll. Personalities are defined and divided by social media, or even operating systems—lifestyles simplified to “Mac or PC.” The static hum is ever-present through lightbulbs, watches, self-powered vacuums, electric toothbrushes, and other technologic material culture. Hsu notices these objects evolving the contemporary culture responsible for establishing them, saying, “these objects were made to help us but they have changed the world and therefore changed us.”

Hsu does not offer a critique of the intimacies of humans and technologies. Liquid Circuit is merely a mirror to it—more hopeful than resigned and questioning what it means to exist in the world where entire exchanges and relationships can live in the technosphere. It’s the age of the techno-sublime, and the colossal, neon bio-machine reflects the relationships between “people, their desires, and their systems.”

– Laura Moran, 2016 – 17 E. Gerald and Lisa O’Brien Curatorial Fellow. Taken from the Spring 2017 Newsletter.