FEATURED ESSAY

Some of the most striking World War I posters in the Fight or Buy Bonds exhibit were directed at mobilizing women to meet national needs. The massive mobilization required by twentieth-century warfare put great strains on American society. With four million men taken into the armed forces, labor shortages developed in many sectors which women helped fill. The expansion of the forces and the fighting itself created the need for thousands of women to fill clerical positions in the Army and Navy and to provide nursing. Military requirements for foodstuffs, fuel, and other economic resources led the government to exhort women to economize in household consumption. The posters in the exhibit vividly express the widely perceived importance of women’s contributions to the war effort. Public awareness of women’s significant roles in the war also gave added weight to discussions of women’s place in society, their economic situation, and their rights. Calls for better treatment of women workers and for granting the vote to American women gained strength during World War I.

More than 25,000 American women served in various capacities in Europe during the war. They worked as nurses, typists, telephone operators, drivers, and journalists and served in canteens and military recreation centers. The American Red Cross and YMCA recruited thousands of women volunteers for these duties. The US Army was formally closed to enlistment by women, but in March 1917 Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels opened the way for women to serve in the Marines Corps as reservists and in the Navy as yeomen, mostly to replace men in office functions. Still, gender and racial segregation in the military and the civilian workforce remained strong in the United States throughout the war. The Red Cross, for example, refused to accept African American women as nurses until July 1918 and sent none to Europe; the Army Nurse Corps did not accept them until December 1918. During the war the YMCA recruited less than two dozen African American women to work in canteens that served some 200,000 black soldiers.

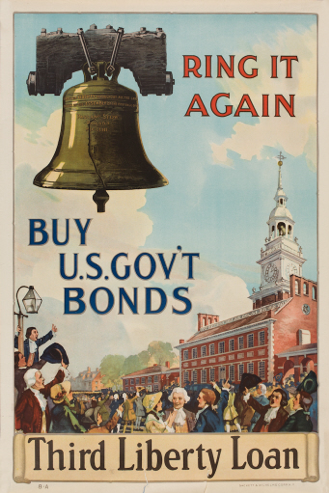

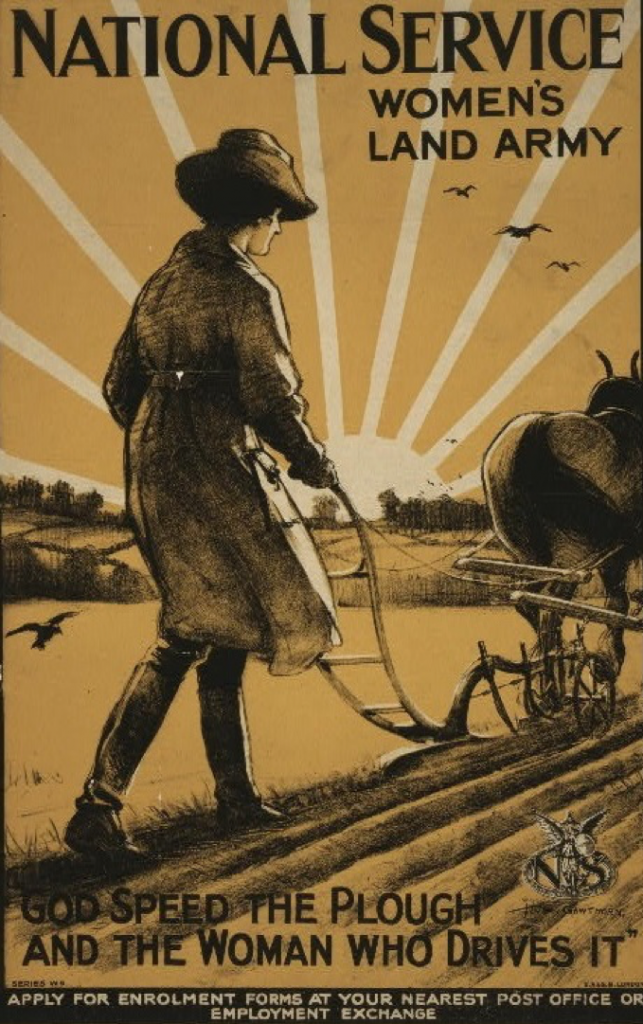

Millions of American women of all racial and ethnic origins contributed to the war effort on the home front. The government’s wartime rhetoric spoke of civilian work for the war at home as a critical second front and considered women’s contributions essential. Still barred from most skilled industrial work and heavy labor, women replaced men in many offices, in railroad yards and bureaus, and as streetcar conductors. Labor shortages in agriculture prompted an initiative led by college women in 1917 to establish a voluntary Women’s Land Army, following the model of the government-sponsored W.L.A. begun in Britain in 1915 [see images from the American and British organizations]. More than 15,000 American women eventually participated.

The wartime developments sparked a strong public awareness that women were playing a more important role in the American workforce than ever before, but World War I, in fact, did not have a genuinely transformative effect – certainly not like that of World War II. World War I saw rather a continuation of processes that had already begun in the previous two or three decades, particularly the growing engagement of women in white-collar work and some professions. Otherwise, there was no sharp change in women’s social and economic roles simply due to the war. They continued to find employment primarily in occupations marked as women’s work, such as textiles and clothing manufacture, food-processing, laundries, and clerical positions. The overall participation of adult women in the workforce did not jump up sharply by the end of the war. Many industrial unions, like those of railway workers, opposed the employment of women in their sectors during the war and were eager to push them out after 1918. African American women continued to face severe discrimination in employment.

The increased public awareness of women’s role in the workforce and the importance of their contributions to the war effort did, however, provide the opportunity for activists to redouble their agitation for equal rights for women in employment and as citizens. The movement for women’s voting rights gained increased traction in the US during the war, and as a result the nineteenth amendment to the US constitution was finally ratified in August 1920.

Some readings on American women in World War I:

Lynn Dumenil. The Second Line of Defense: American Women and World War I (Chapel Hill:

The University of North Carolina Press, 2017)

Lettie Gavin. American Women in World War I. They also served (Niwot, CO: University

Press of Colorado, 1997)