Hear from Lake Street Truth Collective Truth & Repair facilitators Quito Ziegler, Jennings Mergenthal, and Kya Concepcion about their work engaging the Lake Street community during summer 2021 on the former Roberts Shoes lot on Lake St. & Chicago Ave. Moderated by WAM's curator for creative collaboration, Boris Oicherman. This event was recorded on December 1, 2021. Learn more about the Lake Street Truth Collective's Target Studio Residency >>

Boris Oicherman: Hello, and good evening everyone. Welcome to the Weisman Art Museum’s conversation about the Lake Street Truth Collective, which was a series of activities and a collaborative that was set up last summer on Lake Street in Minneapolis. Before we begin, as always, we begin by acknowledging that the Weisman Art Museum stands on the traditional and contemporary land of the Dakota people. We aspire to honor and respect the indigenous peoples past, present, and future by incorporating indigenous knowledge in our work and establishing meaningful and reciprocal relationships with the carriers of indigenous knowledge and with communities. We must also acknowledge that the land acknowledgement is merely the first step in a long and complex process of reconciling with the colonial legacy of our institutions. I would like to state our commitment to this process. I would like to thank the following organizations for the support of The Truth Collective last summer: The Graves Foundation, Black Visions Collectives, Lake Street Council, and Allina Health. We will open the presentation with a round of introductions and then Jennings will talk about the history of Lake Street, followed by Quito's presentation about the project and the activities of last summer, Kya's response, and that will be followed by the Q and A. And you are already welcome to submit your questions and responses through the Q and A function in the Zoom. You can also upvote questions submitted by other people, and that will raise those questions to the top. We will have live transcription going on, but you need to enable it. If you want it to work, you enable it by clicking the live transcript icon on the bottom-right on your screen. Let's do our introductions. Jennings, take it away.

Jennings Mergenthal: Hi, I'm Jennings. I didn't know I was gonna be asked to introduce myself first. I thought that was gonna be Quito— so I was gonna use Quito's time to think, but here we go. I do historical type research. I helped with historical research this summer and discussion facilitation. And that's me.

Quito Ziegler: Okay, hi everybody on the Zoom. I am a fourth-generation New York Jew who has a very long-term involvement with Minnesota, Minneapolis, the Twin Cities. I first came as a Macalester student in the '90s and lived there through the mid-aughts and have just a long and deep love for the land. And over the last 25 years, I've done a lot of community organizing, got my start on Lake Street. I'll tell you a little bit about that later. A lot of projects are at the intersection of art and social justice, and I guess that's all I need to say for now. Kya, over to you.

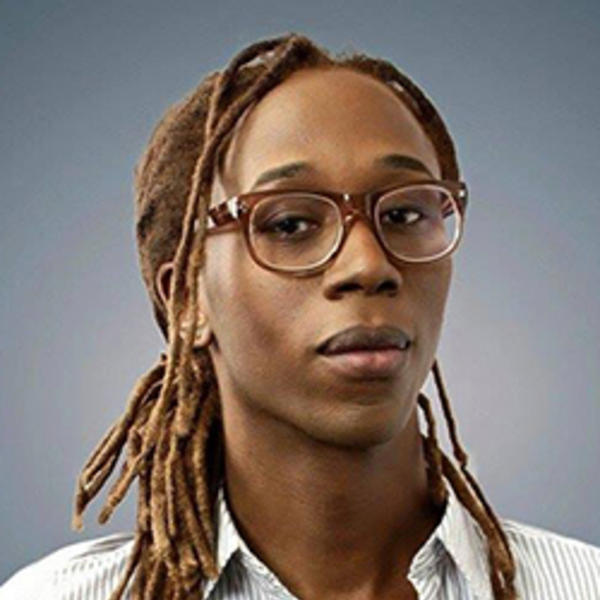

Kya Concepcion: Over to me. My name is Kya Concepcion. I'm a graduate student at the Humphrey School of Public Policy. I also work on campus. I've been here for about eight years. I think I have a deep background in community organizing, facilitation work, which is kind of how I got pulled into this. That and deep, deep, deep love of Lake Street, of South Minneapolis as a whole. I'm kind of just joking when always say that I'm in love with South Minneapolis, but I really kind of mean it.

BO: Thank you all. And I am Boris Oicherman, I'm the Curator for Creative Collaboration of the Weisman and curator of the Target Studio for Creative Collaboration, which supported parts of this project over summer. And Jennings, take it away. Floor is yours.

JM: This time I knew I was gonna get called on. So, the Lake Street Truth Collective, truth and repair team—that's us. Last year, a number of things happened; most of them were bad. This work grew out of the uprising and the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd by the police in 2020 at the corner of 38th and Chicago. In the resulting uprising, there were a lot of protests and a lot of public displays of anger and frustration, particularly along the Lake Street corridor— and in particular in the area that we came to work at, at the intersection of Chicago and Lake Street. I think it was important and powerful for us to work in this particular space at the corner of Lake and Chicago to build community and understand the histories that brought us to the present and how they continue to influence the world we live in, in a number of ways. That is the part that I did research on, Lake Street.

I've always thought those split-down-the-middle historical images with the past and the present were cool. It turns out they're also a pain to make. It took a lot of Google Maps Street View to find where the buildings lined up. But as Boris brought up in the land acknowledgement, the inescapable context of this work and this society is that this is Dakota Land. In 1837, the Dakota were forced to sell their lands east of the Mississippi to the US and in 1851, were forced to sell much of the lands to the west of the Mississippi. Minneapolis itself was founded in 1850, and the Dakota were exiled by the state government in the aftermath of the Dakota Uprising in the 1860s. The Dakota did not in fact all leave. This continues to be Dakota land, land that has been continually occupied and cared for by Dakota people. And that's not gonna change. But Minneapolis is the unfortunate context that much of this existed in. This is Lake Street—back to my Google Maps perusing. This is Chicago. So, Lake Street in early Minneapolis was not in Minneapolis. This was far out in the boonies—no one would live here. It was a street that sort of rich Minneapolitans would go to the lakes on. To contextualize where this work happened, we were at the intersection of Lake and Chicago, right there. Additional contextualization, George Floyd Square is to the south here.

This area was the site of a Dakota settlement, Heyate Otunwe or Cloud Man's Village from 1829 to 1839, sort of a sedentary agricultural settlement where a number of Dakota under the direction of Chief Cloud Man set up a more permanent agricultural village to help survive a variety of brutal and unpleasant winters. In 1839, the village was abandoned in part because they had survived and they didn't need to live like this anymore. And in part because there were a lot of settlers around here. As Minneapolis develops, as many of you are familiar, it benefited from a massive influx of Scandinavians throughout the late 1800s. And being not especially desired by the citizens of Minneapolis, the Scandinavians were made to live out in the middle of nowhere, which was in Minneapolis at that time, along Lake Street. This is where we get the origins of places like Ingebretsen's and the American Swedish Institute. This is a trend of immigrant populations not especially desired by the dominant culture in Minneapolis being made to live along Lake Street. And we will see parallels as we continue through our criminally brief rundown of history.

One of the most visible signs of Lake Street is the Midtown Exchange, which was a Sears. In 1928, about 40 homes were destroyed to construct it. And it employed more than 2,000 people and really helped to bring people through the Lake Street corridor. People would come along the streetcar, going to their jobs. They would stop at stores. It brought a sort of revitalization to what was at that point, still considered a sort of undesirable immigrant neighborhood. And this is another trend that we will see of destruction of homes in the name of revitalization. And sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn't. And most of the time it's racist, but more on that later.

So we're gonna talk very briefly about redlining. This is a housing policy that deeply affected Lake Street, which you can see as a sort of horizontal yellow bar on this map. Redlining was a federal policy in the '40s that extended mortgage assistance and completely coincidentally, and by accident, it extended mortgage assistance mostly to white people who lived in more desirable neighborhoods and not at all to people of color who did not. This helped create things that we still see the effects of today, like the racial wealth gap and gaps in homeownership. In the 1940s, home ownership rates for Black residents in Minneapolis were about twice as high as they are now. Most other groups have seen steady increases in homeownership. The Black homeownership rate since 1950 has been cut in half. And redlining affected Lake Street because it was a less desirable neighborhood. People around Lake Street were not given the financial boosts to allow them to purchase their own homes, so Lake Street remained a largely renting neighborhood and this became particularly intersected with race as by the 1940s. The Scandinavian immigrants who had been made to live along the Lake Street area were now conventionally accepted as white. So they were able to take advantage of things like redlining and new home construction in the newly created suburbs and move out of Lake Street because they had assimilated into whiteness in this way. And if you were not white, you didn't get to do that. Here is a layer of where people of color lived in Minneapolis over where redlined areas were. It matches distressingly well.

Another thing predominated that widened this housing disparity gap was racial covenants, in addition to the sort of implicit biases of banks not extending loans to people of color, there was wholesale language inserted into the deeds of property that said, "White people can't live here," which helped create and cultivate predominantly white suburbs with the intent of keeping them that way with the goal of white people being able to chase the American Dream and that way of moving out into the suburbs in newly-created homes and taking advantage of homeownership and the stability that comes with that, and people of color being concentrated in cities. During the '70s as white residents left the cities for the suburbs, there was a decline along Lake Street and in most cities, seen nationally. This decline has a number of causes, and we don't have time to discuss all of them in great detail. But one of them is racism and white flight.

As more residents of color moved into these areas, more white residents would leave. This became a self-perpetuating cycle. This is a protest of anti-integration from Minneapolis in the '50s. I think it was important to me to include this in this presentation, as well as in the galleries that I helped create which this summer people looked at, because this is the sort of racist moniker sign-waving that we like to think doesn't happen in Minnesota because we're too polite, we're too nice. And that is a lie that white Minnesotans tell themselves. Racism is here just as it is everywhere in society. That is largely fundamentally inescapable because of how the society has been constructed.

Another cause of decline in Lake Street was the construction of interstates. The construction of interstates and large infrastructure projects is not neutral in this society because of who is doing the constructing. The central area of Lake Street was effectively fenced in by 35W and the widening of Hiawatha to separate it from East Lake and West Lake, which were considered whiter and better neighborhoods. This obviously didn't happen just in Minneapolis. In St. Paul, there's Rondo, and there are examples nationally of infrastructure projects being weaponized to disproportionately affect people of color. In the '90s Lake Street experienced a revitalization as more migrant and immigrant communities from Mexico and Central and South America, as well as East African refugee and immigrant communities came to Lake Street.

Another very visual example of this is Mercado Central, which opened in 1997. Lake Street has experienced a revitalization as more people live and work along there and attempt to make and maintain communities. But as always, these communities in many ways remain segmented and divided from each other, or don't talk to each other, or have prejudices against each other. And this is one of the things that we wanted to solve entirely for our work this summer. That was a joke. However, the other side of revitalization is trends in gentrification. There is now sort of a reverse white flight as white residents from the suburbs now seek to move back into the city. They move back into newly constructed buildings, which increases the property values, which increases the tax rates for people who have lived there for longer, as well as just prices them out of the area wholesale, as they decide to do things like raise rent. Their ability to raise rent is now slightly more limited, thankfully, but we'll see how that plays out. And yeah, so a lot of complex history, a lot of trends, and a lot of intersection of these trends and this is the situation that we walked into this past summer. And to talk more about that, I'm going to stop sharing my screen and pass it over to Quito.

QZ: Okay, hi everybody. Okay, so let me share my screen and continue to pick up the story where Jennings left off. So, my part of the story begins in the summer of 2020 when—oh my gosh—how on earth do you talk about the summer of 2020? I don't even know. I'm gonna start by going further back to just explain some of my history and connection to the place that we were in.

So, 20 years earlier in the summer and the fall of 2000, there was a big public art project on Lake Street called Lake Street USA. So the photographer, Wing Young Huie, had spent years documenting the people in the neighborhoods surrounding Lake Street. And that summer we put up hundreds of his images back into the community where it was taken. This is what it looked like at Roberts Shoes. It was in hundreds of store windows, it was on the side of the 21A, and it was on the face of the Sears Building, which at the time (the building that is now the Midtown Exchange) was quite dilapidated. Now, I was a 19-year-old, 20 years old or so when I met Wing and started shadowing him on Lake Street. So I landed on Lake Street at that time, and really fell in love with the place like Kya talked about falling in love with South Minneapolis. I fell in love with Lake Street and spent probably three years with Wing walking up and down Lake Street, figuring out where these pictures were gonna go and then producing the exhibition, and really coming to know and love Lake Street a whole lot.

In the years that followed, I learned how to be a community organizer. I was really inspired by the work of connecting with different people on the ground. And for several years in the mid-aughts, I organized a coalition with a number of other folks called the Minnesota Immigrant Freedom Network. I was the co-director there for a few years, thinking a lot about solidarity with immigrants, how non-immigrants could show up to support immigrants in our community. And that also meant spending a lot of time on Lake Street at the Mercado Central with the Latino communities up and down Lake Street.

In the interim, I went home and did a whole bunch of queer stuff, but would always visit my friends and come back through and maintained community in Minnesota. As I've become a professor in the last few years in New York City where I live, summer visits became sort of part of my habit. I think I've come back every summer for the last 10 years, maybe longer. So in the summer of 2020, when this happened, and a lot of the roots of where abolition conversations have been happening really strongly in the last like 10, 20 years… I’ve been in queer community and trans spaces where transformative justice wasn't just a thing, a concept that nobody knew anything about, it was where it was being practiced and figured out. And I don't know, queer community organizing could say a lot about it.

But I came back to support friends that were involved in the organizing and City Council members of the neighborhood, and tried to figure out what the conversations were and how to bring things together. I was involved behind the scenes in a lot of conversations around the Powderhorn encampment, around George Floyd Square—community safety conversations, a lot of accountability conversations. And I just kept thinking about this story that I had heard, a film that I saw called “Fambul Tok.”

In my work as a photographer I had crossed paths with the filmmaker Sara Terry and I just really could not forget the story that I had heard about Sierra Leone. And so, the story about “Fambul Tok” is in Sierra Leone, where there was a very brutal civil war and when it was over, people in communities were living in villages with people who had caused a lot of harm to each other, but they were from the same place. So they had to sort of continue on. “Fambul Tok” was a way that they developed to have conversations as a community about the harm that had happened. So, on a government level, there was a truth and reconciliation process that had happened. But at the end of it, they end up putting maybe eight people in jail for life which is one way of addressing a genocide, but the scars and the wounds that people felt at the community level were not given space and time for healing. So, there was this practice that they developed.

Over the years, I had exposure to a lot of different, I don't know... I've learned a lot about truth and reconciliation processes over the years, just like a weird fascination of mine, but the one in Sierra Leone always felt different because it was about having these conversations at a grassroots level. And the basic principles. So I started thinking about it a lot. As I heard about more, all of the community tensions that had surfaced in the uprising, none of the things that people were talking about were new, but there were these really deep tensions and people were living side by side with people that they really like...there were just a lot of factions, a lot of fractions and somehow, I was thinking about it and there are some things that I learned.

I started just thinking about how to code-switch it. Like, what did they do in "Fambul Tok" that worked? Because the truth was it spread to hundreds of villages, many, many people healed, the whole communities were able to heal through this process. But what did it mean in Minneapolis? So, I tried to distill the things that I thought were powerful about that model as it related to Minneapolis, and there were principles. Okay, so the first one is that like, community repair can't be a top-down thing, it doesn't belong to the government, it belongs to the people and the people have to do this work themselves, or else the problems aren't gonna go away.

The second principle that they really hold to is that, “There's no bad bush to throw away a bad child.” But you have to consider a community as a whole thing. And that relates to wisdom from Transformative Justice, which teaches us that, “No one is disposable.” That you can't just cancel people or send them to jail or whatever, or shoot them in the street. If we are connected to the same piece of land, if we are living in community with each other, then we need to think about that more holistically. And that there aren't any shortcuts for the process that you have to go deep and have really difficult conversations, because that's where you're gonna find the real answers. As long as you're not getting into the real shit, you're not gonna fix it. It's just gonna keep happening over years.

The third principle that they really adhered to is that people need to define justice for themselves. So this is different from a law-and-order kind of perspective, where we trust the government to make decisions about justice. It's like, no, we have to figure that out for ourselves. And we all have to arrive to this as equals.

The fourth one, the fourth principle that I thought was really important, is about truth and repair—that you can't just have conversations where the truth-telling happens, you have to link it almost immediately to the work of repairing from what you've learned from the truth. That one needs to be intrinsically connected with the other, because if you're just stuck in the truth mode, then you're still just talking. Repair means taking action and trying to do that work.

And let's see, there were things that they did there that the way that "Fambul Tok" worked in the villages is that they would do a whole lot of process that would lead up to a big night where there was a bonfire and people ask for forgiveness in front of the community. And it was a whole thing. And then the very next day, they would say, “You need to start working on community projects together.” They also planted peace trees or designated a peace tree or a site. So, you need a place where people can come back to, to keep having those conversations, because it's not like things get fixed in a bonfire. It is an ongoing process that takes place over time. They also spoke about having sports teams compete with each other, but like as a healthy way to foster community unity and competition and address some of the mistrust between people. If you're playing on the same team, then that helps.

The last bit that I took from it was that you need a formal process. You can't just expect that this work is gonna happen on its own, but that there needs to be a process to address what is wrong. And that process needs to move at the speed of trust. That's like a beautiful phrase from Black Lives Matter, where I learned that phrase. But you really gotta go slow. You have to build trust if you really wanna get to the root of what's wrong and what's been harming us and how we've all played into these harmful systems. You'd have to do this one step at a time. But with a process, there's a beginning and an end to it. There will be work that continues from it, but that you can't just leave it hanging, that you have to have a start point and an endpoint. And that is gonna be long-term.

We spoke with... So in the summer of 2020, I arranged a phone call with the person who dreamed this process up in Sierra Leone and who is still the leader of "Fambul Tok", which is now a very large network of places all over. I think the African continent has also done similar work together and he really warned...So I arranged a conference call with him and with City Council members, and with other people who were involved in grassroots work to sort of just help people understand this better. And they said, “You gotta be really mindful of government involvement.” And it also came from some learning from a process that they did in Greensboro, but they say like, “You gotta be really mindful of it. Like you can't let the government run it, or you can't even let the chiefs of the village run it, that it has to really belong to the people or else people aren't gonna believe in it."

I also took a bit of wisdom from them about facilitation because as a person who does not live in Minneapolis all the time, I felt really sensitive about even proposing that we do a process like this. But they spoke in “Fambul Tok” about how outsiders can create and hold space and invite and connect people with each other and build connection to the next levels of governance or the next level of infrastructure...And I just sort of took this as like, okay, here are the boundaries of what I can do and not do as a person who doesn't live here all the time, but has a really deep love for this place. And I wanna see, I wanna contribute how I can to the healing of the community after some of the hard things that happened, but that are related to these much longer-term dynamics that Jennings spoke so beautifully about. And they said also when we spoke to John Caulker from "Fambul Tok" last summer, he said, “You're not gonna get the whole city to do this all at once, but do a circle, call start in one place. Let it be a snowball effect.” That the conversations themselves need to be intimate anyway. So you can divide it up into zones or different areas, or think about it this way.

So, we spent all winter between the summer of 2020 and May, this past May when I got back to Minneapolis after being home for the school year and living my life here. And the way that I just thought a lot about how to code-switch it. Like the context of Sierra Leone is very different from Minneapolis and you're like what are the similarities? And what are the differences and how do you bridge that? And so, what wound up being the result, and this is the basic schedule that we went through was a series of community dinners on the corner of Lake and Chicago, in what used to be the Roberts Shoes lot. There were these eight community dinners that we held that walked through a series of conversations that we thought were important to have and that we thought would help us get to the heart of some of the things that needed to be touched on. And we carried over the principles of “Fambul Tok.”

So in designing what those community dinners were gonna look like, the first part was about community control. We thought about relationships to place and geography, which also relates to principles of decolonization, which really ask us to love and care for a piece of land that we are connected to and for the entire ecosystem that surrounds that land. So it's not just about the humans, it's also about the air and the water and we had an opportunity on Lake Street this summer to participate in organizing around Line 3—or stopping the Line 3 pipeline—which is now flowing underneath the Mississippi River that also connects to Lake Street.

So there was a really direct connection there with that. But we looked at the corner, we understood that we were gonna do this work in the Roberts Lot. And we looked at a map and we sort of were like, “Okay, what is almost like the spiritual neighborhood that is surrounding this place?” And we drew sort of a circle around it. So it went from 35W to—I can't quite remember, like, I guess the specific boundaries are lost in my memory, but we set out a specific area and our ambition was to actually door-knock at every home that we could. We were gonna flyer every single door and talk to the people within that neighborhood. But we only got as far as we could. But everyone who was in The Collective and who was part of the Lake Street Truth work were people who either live, work, or who just really love Lake Street. But all of us had a connection to the place itself. It wasn't about inviting in people to observe us or people from other neighborhoods or whatever. It was like, "No, this is our community." And we need people who felt like this was a community that they were invested in for the most part, more the people in our collective. The community wholeness principle.

So understanding that we needed to consider everyone there meant throwing away ideas that we had about networks that already existed, and really just looking at like okay, every human being who is attached to this piece of land, how do we make it accessible for all of us? And understanding that part of the beauty of this area is that it is incredibly diverse and there's just a lot of different people, backgrounds, and things. So accessibility was something that we really prioritized.

Starting with physical accessibility, we built out the space, we brought in ASL interpreters for every event that we had, we had people available to help translate and interpret into Spanish and Somali. If those folks showed up, we tried to remove as many language barriers as we could. We were open and welcoming to everyone who walked through, whether they own a home or a business, or were unhoused. Everybody got the same food. We provided free food, we kept that accessible. And we planned to have art from every cultural community who passed through Lake Street. And I think we nailed it, but we were trying to do a lot of things. And some of the art kind of got a little sidelined or happened later in the summer, and not when we were having the dinners or whatever. But our goal was to make the space feel really accessible and approachable, and welcoming.

We refused to accept that racialized identities defined what community was. We really understood that there are factions within every identity group that people consider, especially racialized identities. And so, we really dealt with people on an individual basis. I already spoke about the door-knocking. And it's interesting because the door-knocking that we were able to do, and the flyers that we handed out, was how people came to know and came to be in the space with us. People came holding the flyers and said, “Somebody left this on my door. What is going on here?” And then they would come back repeatedly because there was a vibe that we were trying to perpetuate. We were very open to unhoused people, drug users, sex workers. They were full members of our community. And we all sat together and ate together. Everyone was welcomed there and we really were very intentional about treating people all the same and considering all of us part of the same community. And we had a DJ and everybody danced together. That part was really cool.

In terms of us defining justice for ourselves, we had a really strong, “We keep us safe mentality,” so we did not hire security guards. We did not welcome in the police. Instead, we trained everybody on community safety practices. Manuel, our community safety organizer/trainer, was amazing. We emphasized organizing with local groups. We tried our best to invite everyone who was involved in it. We tried our best to really keep it from the neighborhood and really keep it tight. Let's see. I don't know. I don't have to give every single bullet point that's on these things. Sorry, you guys, it's kind of thorough.

Truth and Repair. Okay, so this phrase was one that I like really spun out about—I spent months and months thinking about this because truth and reconciliation—I was like, “I don't feel like people are ready for reconciliation, there's too much work to do to get there.” And thought about a reparations framework, but I feel like there's reparations in the mind comes back to money a lot of times, and this wasn't just about money and repaying people, even though I think that that is part of it. And in my mind, I really settled on the word repair. That felt like that it was like an active, a way of really actively addressing the truths. I think that we did better at dealing with having these conversations that were rooted in truth and the area of repair.

We pulled this off really fast and are now spending a full year planning whatever we do next summer. We provided historic context. So some of the slides that Jennings talked through, all of the slides that Jennings talked through in their history that they gave were printed, and laminated, and put up as an installation in the site because we wanted people to have that context and that truth be available to say like, "This is what we understand is the history. This is the truth as we know it.” And we really understand repair and connection with other community projects. We don't have to be the ones to initiate the repair work because there's so much work that people already do in our community. But we're about connecting with those projects that are aligned with the truth as we understand it. And as far as where we're at in our process, we know that our work isn't done yet. And we're not sure what's ahead, but we know that we're gonna be working to refine the model, to connect with each other, to reflect on what we learned, and some of the community dynamics that we uncover that perhaps could use some more conversation. And yeah, I'm gonna pause my part from here and turn it over to Kya to talk about what happened.

KC: Yeah, I'm gonna share my screen and then see if I can figure out how to do this. I got this. Share screen and then I'm going to, yeah. And I'm gonna start my slideshow. Okay, so we have this, I really wish that we had time for both Jennings and Quito to hash out the way that we as The Collective received it, and we have this complicated, detailed history that you only receive a sliver of. That history informed us around the displacement of different peoples, and redlining, and how Lake Street had been divided, and broken apart, and put back together, and rearranged by gentrifiers with their intent. And then Quito with this idea, looking at what truth and repair looks like and why Minneapolis was a prime candidate to participate in this process. "Why was this right for us?" became my question and I was here in 2020. I live in South Minneapolis. And I remember the hardship, I remember the fear, I remember the pain. I said earlier that I'm in love with South Minneapolis. I've lived abroad, I've lived in a number of cities, but it is Minneapolis, South Minneapolis that has my heart. And I just so clearly remember understanding why Minneapolis was on fire and that it needed to be on fire, but also being heartbroken at watching my neighborhood burn. And I know that so many people can understand and engage with me at that moment, torn between, is my house safe? And also I've got to be in the street helping my people who are out here doing what they think is best. This next generation.

So we know that pain is real. And we have a group of people who understand that, that pain is real. And that's where the truth and repair came in for me. How do we talk about what happened in 2020 and frame it with the truth? How do we talk about the complex narrative that went into what happened? I think that was a great example talking about how this tension that sparked, that ignited this flame that became a fire that burned down Lake Street didn't happen in a vacuum. There've been years of systematic and structural institutions at play that led to this powderkeg of this perfect moment, almost with COVID, with the killing of George Floyd. But it's not just the killing of George Floyd, it was the killing of Philando Castille, it was the killing of Jamar Clark. And I'm sure you all are thinking of names that I haven't said yet, and that I could continue to name them for the rest of my time.

And so, with these things in mind we got together, just a bunch of them they queers hanging out on this porch, it looks like. I'm gonna start with this image. We started talking about this and we started listening to what Quito was saying and we started trying to think about how we wanna move from here into this space and invite people. And this seems so simple, but it became something that was so powerful. You see the canopies here, you see the Global Midtown Market behind us. Us working as programming was starting, still working on accessibility, asking ourselves questions, "What did we get right?? "What did we get wrong?" The pilot dinner that started it all. And the questions that we asked. And the people, they came. We invited people out and they started to show up and they wanted to talk. And you can see that when Quito talks about the truth, you could see and understand that the people that came out, looked at the flyer, talked to whomever they may have spoken to, heard about this, and were curious and came out of a similar desire.

And that desire was this connection to Lake Street, this connection to South Minneapolis, and this deep desire to try to start wrapping our heads around what had happened. And so, we kept it casual because we wanted to be inviting. And now, when I think back to this summer of 2021. And I think, did we do good work? And I think if we just only fed people, if we fed up to 100 people on any given dinner night, then the work we did was worth it. But we started getting involved with more. And you can see people starting to show up to the spaces, starting to fill themselves out. We've tested some ideas at this point, we've decided what worked, and what didn't work. And so, this process starts to flow and things got powerful.

You see this, one of the installation pieces that Jennings masterfully put together, and this thing started happening as people started engaging the work. People started going through slide by slide and really asking questions. And I remember going up, I worked closely with Jennings to help them get this produced. And so, I read carefully through each slide and that became very important as a facilitator because people were asking me questions. People had curiosity, they wanted to know things around what redlining looked like. You know, a lot of people had never heard of these covenant clauses.

And we had a great time just dragging Joe Biden. It was hilarious, y'all and I really appreciated it. And so, the conversation kept going. And then it got involved. And this picture here I wanna stop and I wanna really give a shout out to all of the youth that worked with us this summer. For me, I had several magical moments this summer, but I will say hands down that one of the most magical moments was to get to work with these at first, very shy, and reserved, nervous youth team that Erica wonderfully brought in and had been mentoring. And I remember sitting them down and saying, “You all are part of this community. You all are experts on this topic.” And I don't think they believed me in week one. And then week two, they were a little bit more engaged, and then week three, they were answering questions. And then by the time we got to talking about housing, they were giving detailed, informed answers to the people that they were sitting and talking with.

And by the time we got to public safety, I remember watching one of these beautiful young people, all of 16 years old—and if this is the future, I promise y'all, we're fine—and we were talking about public safety and we were talking about the history of crime. And at 16, I watched her sit there and she schooled this entire table on the '94 Crime Bill, on Reaganomics, on what had happened. She linked it to a personal experience with her own family, as a way to engage. If that's not community conversation around difficult topics when you have a bunch of, I'm gonna say a bunch of well-meaning white, progressive South Minneapolitans sitting at a table listening to a young Black 16-year-old educate them about why some consider Joe Biden problematic, especially people who come from marginalized identities?

There's Boris everyone, thanks Boris. And it got multicultural in a way that I didn't expect. I learned so much. This is Ifrah. Ifrah is part of the Somali community. And they built these beautiful, magical huts. And I remember when they finished this hut, I wish we had a picture of the finished hut in the slides. I remember going to sit in the finished work. And so, across these cultures, in this moment, the Somali community had reached out and had shared with me a part of their culture, really to engage about the pain that we were all feeling as South Minneapolitans. And so, this is the way it started to just kind of flow and move.

This is one of my co-facilitators prepping the youth and educating the youth before we realized that the youth was gonna educate us. One of these youths would show up at all of our facilitation meetings to help us work out what the programming should look like. And so, we emphasize youth and we emphasize the future, and I think I may have sound-boarded that really hard, but after the summer, I believe it because these kids really, by the end, we realized that we had been educated by them and had not done much educating of them. They were powerful, I'll never get over that.

And then speakers from stratas as far as community organizers to some of our Anishinaabe sibs up North started coming down, people who you know, our Latinx community that had those deep roots right there at that corner, and started to come in to talk about the different story.

When we talk about land and water, Quito insisted that we have to go up north, we can't talk about this land and this water. We need to get with those people who have that knowledge to pass down to us. And it was the same with the Latinx community. They had so much to teach us, especially, for me, I'm saying for myself, to teach me about what truth looked like at the corner of Chicago and Lake, for the Latinx community.

And so, it became this moment where these different communities came together. And then we talked about housing, and I think most people will agree that the conversation about housing got so very real. If you see that look of attention on our community guests’ faces, if they listened to our speaker, it was that intense. The truth is, she began to speak and this brother began to speak. I remember I had to go up after this brother and say something about housing, and I realized that he had...the streets were talking. And when you can capture in a moment that the streets are talking, I mean, that's when this kind of work does become art. I mean, it becomes high art because the streets were talking to everyone that was there and these hard conversations started to happen. And especially around housing, I just remember watching people who were struggling with housing, people who had not had housing, likely people that didn't have housing talk to some of these homeowning, well-meaning South Minneapolitans.

And that kind of intersection where those different stratas of community are getting together with food and the importance of food and talking becomes a super powerful moment. And then these kids who just absolutely just executed out there. Like I said, it was wonderful. From the music, to the kids, to the youth basis, but just seeing what the community looked like.

This is just us being our queerdo selves, doing what we did best over the summer, which was to just try to create a space where we could start talking about what had happened in a more comprehensive way if possible, if that makes sense. We could really start getting into what did it look like in Powderhorn Park when suddenly there were tents up everywhere, or when those tents got torn down, what do you know about the Sheridan? What do you know about housing? What do you know about housing laws? And how we've arranged different groups and different sets of people to live where they live right now and how we're rearranging that right now.

And so, now I'm just gonna spend some time going through some of the key themes and concepts that we saw from those dinners. And so, some key themes, connectedness and belongingness. That was something that happened on the porch the very first slide when we really decided that our aims, that our goal was gonna be to create this space where people felt connected and they belonged, and then to see the diversity that came out and they shared that feeling, and the laughing, and the food, and the engagement, I really felt like we can check this one off and say, "Mission accomplished."

Healing from trauma. I don't know what the healing part looks like, but we definitely started the conversation about the trauma that underpins some of the nice facade that we put on top of our lives in South Minneapolis. And I'm definitely speaking to me with some of these criticisms. I am a well-meaning South Minneapolitan progressive, I'm one of those too. Some key things that came out of the conversation like I said, our Latinx community really showed up, our East African community, to a lot of the diversity that we see past those communities, undocumented immigrants have had uneven access to services and programs, and that became especially real with COVID. And we heard stories about it. The legal status in this country is long overdue. I just remember talking to someone and them just breaking down for me how it was amazing, how certain portions of the community had gone from illegal to essential, and then back to illegal again, in quick strides. And what did that say about us? And it became a true learning experience.

And then when Anishinaabe sibs, who when we went up to Shell City really did engage us. And I really had a spiritual moment up on the water, but then they came down and started to talk. And then those concerns started to be reflected back. And we saw people come from stratas of high academic institution, institutions to some of the people that have been on the ground, up water protecting and doing their work and as always. Shout out to my water protectors, big shout out to my water protectors, always.

Housing was one of the most powerful themes that we saw and we talked about. And I think it was really a moment for South Minneapolis when, with the best intent, we said, "We're gonna house all these people." But then when we had to look at the reality of homelessness, those same people who invited them down to Powderhorn Park, I'm certain, you know, call the institution that would come and bulldoze those homes over. And so, from the Sheridan to Powderhorn to, I remember last summer, 'cause like I said, it wasn't good enough for me and Quito, for Quito and myself to just say, "We're gonna talk about water." We had to go and get schooled on it. And it wasn't enough for Quito and myself to say, "Hey, we're gonna talk about housing."

If you told us about a situation in Minneapolis where there were tents going up, me and Quito, with as much respect as we could, and as much mindfulness as we could, we were going there, we were gonna be there, we were gonna go and look. Not always enter respectfully if we felt welcome, we would navigate the space. And it wasn't just about looking, it was about talking to the people and it was about really understanding what that looked like, because we couldn't talk about it in earnest if we hadn't looked at it in earnest, if that makes sense.

Public safety was this amazing moment where youth facilitators could have handled public safety by themselves. Just the way that Joe Biden got dragged from the installation piece all the way to out of the mouth of a 16-year-old really brought us back home and grounded us in this question that I had. One of the first conversations that we did about Lake Street and what is sacred about it? And I remember thinking, what is sacred about Lake Street? And really trying to quantify that in my mind and trying to find words for that. But it really came out to me and the people of Lake Street are what make it sacred. And the people are land, and I believe that. So it all made sense to me. That's my time.

BO: Thank you. Thank you all so much. There are questions already in the Q and A and I will get to those in the moment. Also please, everybody submit more questions and we will try to respond to all of them. My question, kind of opening question to all three of you is—and I'm not sure this is even the right question to ask—but what do you feel has been accomplished last summer? And how do you project that into the future into the next summer? What is the process of planning the next summer like for you?

QZ: I can answer this question after a conversation I had the other night with Kay, who is one of our other facilitators. Also Kya, I think you gotta stop your screen share, I think.

KC: I am trying to do that right now, I'm on my screen. There we go.

QZ: Okay, good, nice to see your face again. We're gonna have a retreat soon. We're starting to plan it as of next week. We are going to start planning a retreat. You guys are about to get an email about this. But we know we wanna do this again. There are about 100 different directions that we could go into, whether it's returning to the exact same corner and doing the exact same thing, but different, whether it's facilitating community conversations, addressing some of the factions that came up and trying to go deeper. Whether it's, we're connecting with North Minneapolis and trying to understand how we connect to the emergency that's happening there and how to bridge what's happening in South Minneapolis, and what's happening in North Minneapolis and try to sort through that. There's work that we can do in sharing this as a model, there's and documenting it, and getting the word out about what we're doing. All of this is part of conversations that we need to have. There's specific work around homeless encampments that we can do, and then the housing question. Yeah, so lots of different directions. I can say that almost all if not all of the people who are involved in producing this project last summer, the entire Lake Street Youth Collective is back in for round two. The work was really impactful for all of us and just, we are setting some time aside in January to really come up with what direction we wanna go in.

JM: We're also gonna try to start planning things more than 24 hours before we have to implement them. That's a big goal. We would all wanna see if we can get that up to 36, maybe even 48 hours.

QZ: We will never have eight dinners in the same month again.

KC: I mean, by the end our workflow was so clean that I mean, with Kay on deck, we could get together and be like, "All right, get the word." I mean, before Kay got there, obviously we're chatting, and chitting, and we could go on forever. And then Kay gets there and it's like, "Get to work." And we were on it. Kay's implementation was critical this summer. It really was.

BO: Jennings, there's a question for you. "At the same time the Scandinavian community was forced to leave Lake Street, where was the Black community for us to leave at the same time?"

JM: Not in Minnesota. That is my flippant response. But Minnesota did not have any sort of substantial nonwhite population until or after indigenous displacement in the 1850s. There was really sort of a large period in which this truly was the Great White North. Communities of color that did exist were largely in Rondo in St. Paul. That is where Pierre Rondo, a French fur trader and his mixed-race wife settled in the sort of less desirable area. And that is where sort of the most marginalized people in the Twin Cities area were. After the Great Migration, the Twin Cities did see an increase in Black communities. But by the time of the Great Migration, Scandinavians had become white and could take advantage of things like racial covenant housing, and suburban communities. Yeah.

BO: The next question is for Quito. "You at times say ‘I’ and other times you say ‘we.’ How much of the adaptation from Sierra Leone, the process, was developed by you? And how much by the neighborhood?"

QZ: Welcome to my crazy boundaries. Okay, there's the theory of what we're doing and then there's the way that it played out. Okay, so Kya...

KC: So yeah, do you want some help here? I got the assist for ya.

QZ: Yeah, please.

KC: So, yeah...I think that I and we pushed back and forth with Quito... is part of Quito's...Quito came down with an idea and said, “Hey, I want the Collective to come together and tell me what they think.” And when you see us on that porch working those ideas, without Kay bringing in implementation, without Erica's, I mean, just like ability to read a situation in the moment and play off of that moment, and execute it, and to tell us what ideas are gonna work, and what ideas aren't gonna work. Without Jennings's visual process or Luis educating us on the Latinx community, this thing is just an idea in Quito's head to that point. And it's when Quito comes and presents this idea to the Collective, and we start coming back with ideas about executing it. I mean even from the people who were holding the space to the design of the space, again I think that was the work of all of us based off of this idea, this project inside of Quito's head.

QZ: Yeah, definitely. There was some weird mad professor stuff happening over the winter and really just reflecting. I think there was a benefit that I had of coming for the summer of 2020, spending four months, like really in the trenches and feeling it, and then being able to come back to my attic in Brooklyn and think about it and process it. That afforded me the ability to step back from what was happening in an immediate way and be like, "Okay, what do I know about how communities can heal from stuff like this? And how does that apply to this place that I love?" And I knew, again, I knew that all I could do is come up with the principles for it, but that it had to belong to people, that if people didn't like the idea, then it wasn't gonna happen.

And I was in like half a billion meetings over the course of the winter to try to find support, and I spoke to a number of different community leaders. I had assistance from council members around that as well, but I also knew that the government couldn't own this process and when I got to town in order to pull it off and places like—Boris is a person that I met in one of those meetings—I met with probably 20 or 30 different community leaders over the course of December, January, kind of pitching this idea and being like, “Listen y'all, here's what I can tell you about what happened and what worked in Sierra Leone. And this is what I think we can learn from it.” And people were like, “Well, okay, fine, just go for it, do it.” And Boris was one of the people who heard it and said like, “How can the Weisman help?” And I said, “I don't know.” And he said, “How about this lot on Lake and Chicago and arrange that for us with The Graves Foundation?” But it wasn't going to be real until people made it real. And I knew personally that I would be able to start at a different level and a different conversation if I called in mostly queer and trans folk who have been, I don't know, just that I could trust immediately. And the initial crew of people I met through friends, friendships that I've had for years. And then people made it happen. And the implementation of it, like the way that it came out, is the result of everybody's unique genius that they brought to it very deeply. I am not a micromanager, I'm just, I understood from “Fambul To”" itself. All I could do is create and hold space, but facilitate it and make sure things keep moving along, but I'm not gonna dictate what happens within that space. That's up to everybody. Yeah.

BO: And then there is a question about goals. "Was there a central goal to the project? And if there was, how did it change over time?"

KC: If I may. So, this is something that we talked a lot about and I think we had aims, not goals. We definitely had aims and I think that central theme that we kept returning to, that kept informing the decision that we made from dinner to dinner was, we wanted to create a place where our community along the Lake Street Corridor, South Minneapolis could come together and we could create a sense of connectedness, and belongingness, and start talking about some things that had happened I think that was really everyone goal. “Well, what's your action plan?” And I'm like, well, we have to start with conversations. It starts with... we got the truth, maybe we'll focus harder on repair next year. I don't know, that's a possibility. Or maybe five years from now, we'll get to working on a reconciliation project. I don't know what that looks like, but I really think that sitting down and talking about what happened, letting South Minneapolis debrief was urgently important. And we felt that. And then the community responded to that, like saying, “Yes, we have that need.” Does that make sense, Quito? Did that feel kind of right?

QZ: Yeah, it does. I mean, there's the part of my brain that's like, “I don't know, do I say the things?” Underneath it all is like a really intense desire to unravel the systems of power as we know it, and to provide space for people to get to some of the truths and the histories that are still playing out, which Jennings spelled out really beautifully. We're talking about land that was colonized violently, and genocide happened here, and systems were put in place that are harming us actively. I mean, continually. And so, how do you get my understanding of, how you get to a place where we can actually, and like so many initiatives and so many ways that people think to address it are like band-aids, or like barely addressing the symptoms of the problem as we know them. And so, I feel like my understanding of how we get to a place where we can actually work on the real things that are addressing us is by getting creating space, to get to the root of the problem together, to create a shared analysis as a community and say, “Hey, we acknowledge that all of these things have happened and that these are the truths that we're working with.” Because we can't do real repair without really speaking the truth. And coming to a collective community, understanding with a commitment to a place, those are my understanding of how decolonization works in practice. There are a lot of other spokes and a lot of other ways that it plays out and not an authority on any of this, but this is just by listening and absorbing, like what I understand as where, how a transition could work.

KC: You know, and if I just really could, really you know….the conversation it was, they were...people talked about genocide, we didn't... there was no shying away from tough conversations around homelessness. People got uncomfortable, people were forced into—not forced into these spaces—they volunteered, but people found themselves engaging in these tough conversations, ripping that band-aid off, and getting vulnerable at times. You know, I mean, think about some of the moments where you saw people get real vulnerable around topics that without some facilitation, they may not have even been willing or ready or able to talk about.

BO: Next question. “It's wonderful that these initiatives and efforts are intensely focused on the residents who live in those neighborhoods as they should be. How can those of us who live in other areas in the Twin Cities, but also love Lake Street become involved most effectively and appropriately to support you?”

JM: There's a link in the chat where you can give us money.

QZ: I thought too about people...again, we're still processing ourselves, like what happened, and how we think it moves forward, and what next summer is even gonna be. And we don't have answers for that yet. But I will say that part of me is like, oh, people from other neighborhoods can come and witness and then do it in your own neighborhood, you know? Like, is there a place that you're attached to and that you love that could use this? That's part of the development of this as a model and sharing the wisdom and the principles behind it, because really anybody can take these principles and run with them. And like do what you can in a place that you love. Now, if Lake Street is a place that you love, then hit us up because we will be building a team to make this happen again next summer. And that is an open process. But if it's another place that you are attached to and that you love, what are the confounds of your neighborhood? How do you understand yourself in connection to place and what are the conversations that need to happen there? Go forth, you know.

BO: Quito, question for you. “What are the signs that a community is ready for repair?”

QZ: Ooh, Kya, I see your face. Oh, my gosh.

KC: Good luck, Quito.

QZ: Thanks, fam. What are the signs that people are ready for repair? You put out a flyer and you say, “Come to dinner,"”and the people show up. I think that there is a tendency within the systems that we live in now to spend a lot of time and trying to stop things that are bad and to protest against things that are going wrong. And that a lot of us are in the mindset of, “Hey, people in power, do something different.” And that's really where you go. And then you come up with a lot of elaborate ways to convince the people in power, or to change the people in power. But you're still giving away that power to other people. I think a sign of repair, how do you know that people are ready to repair? People are doing shit because they care about the neighborhood. People are doing things with that, anybody who's showing up to community work, the outpouring of mutual aid. It feels to me like people are ready for repair in some way. People don't want things to keep being bad.

And so, but how to make it good again, there's all these really tangled strategies to get us there. And visions of the future that feel really abstract, but what I’ve learned and what I understand is that you do it by showing up for community, by building a community and being a part of it. And so, if that is a message that resonates with you, then I think that people everywhere are ready for repair—I don't know though, people are kind of busted and there's like a lot of trauma and the need to feel whole within oneself and to repair things internally. And I also see that as being attached to systems around us, because I think like, how the hell do you survive when the system is as stacked as it is. That's nearly impossible. I think the world is ready for repair.

There's a great reading called “Just Transition.” It's like a movement theory that shows up in climate movements quite a bit that talks about how we move from where we are to where we need to be, or from a really extractive, disgusting economy to something that feels more regenerative and sustainable. And there's a phrase that is in it which is, “Stop the bad and build the new.” And I think that as much time and energy as we can start putting into building the new, whatever that is, which I know the seeds of it are rooted in community and connection to place. You know, I don't know how, that's how I know people are ready for repair when they start doing work and you see the bubbling up of that work. That shows that people are looking for these connections and ways to actually do something about climate change is such a huge thing. How do you even combat that? And racial reckonings and the weariness of living through the last couple of years or couple centuries. I think that need for repair, it's visible to me everywhere.

BO: Anyone else?

JM: Yeah, I think out both, of what Quito said, looking at histories and experiences, and how communities came to be, and ways in which these communities were deeply profoundly harmed is a way of figuring out what communities are in need of repair. I think also if people are burning things down, literally, that's generally a sign that something is not going well, unless you're at a Viking funeral, I guess.

BO: Okay, that was a very nice loop to the first wave of immigration to Lake Street. There are two very related questions about what was it that you actually heard? What did people say? How did people respond? Let's start with you.

KC: Yeah, so you mean response to the dinners or like the topics that we heard? I mean there's just like a variety of ways that could work itself out. But some of the responses that we heard to the work that we were doing was just overwhelming. I mean, if you could have saw people who would go from being on the lot to down at the house planning with us, by the next week or the next week later, the volunteer team became, people who had received a flyer ended up being part of the volunteer team and really trying to engage with us about some of the topics that we were talking about, and where this work came from. We ended up collaborating with some of the other art collectives in the city. And then the conversations just got really tough. We covered some of the themes and stuff that we saw and that we heard and I just, I feel like there's probably a stack somewhere of community response. It's like this big, at this point, that really kind of goes through some of what we heard. Quito?

QZ: I heard people really reckoning with each other. I heard housing, and encampments, and homelessness was a thing that just kept coming up. It's so active of a conversation and they were like how to address that. I think it was a question that emerged quite a bit. There was other things that we heard just...sorry to trail off.

It was big, there was a lot, I don't know how to synthesize it yet still. A lot of individual stories like things that come to mind, like Kya coming back and being like, "I'm sitting at this table that is basically where the hip hop shop was. And that was my uncle's shop. I spent years sitting in this spot but it was in a building and now I'm in an empty lot.” That was a thing that I heard, "And thank you for providing that space for us to come back and just be here." From some of the street involved people, I saw that that was part of the question, really. It was like, "Oh, really? Is that...Do you have water? Do you have ice? Do you guys have juice?" Like whatever, there were different things. One guy really needed a belt, so we made him a belt. Other things, people from the neighborhood, people just, I think the fact that it was a space that was not about like, “We're going to extract information from you in order to change the policies of the city of Minneapolis.” That was not a goal. We really just come for dinner, sit with each other, talk to people that you don't usually get a chance to talk to and what else did we hear? I don't know, I don't know. Interpersonal stuff too. Just people getting to know each other that didn't know each other. Jennings, you sat at those tables too. What did you hear?

JM: I sure did. I think one of the things that I heard was people who in these discussions were processing these things for the first time. People who had not been afforded a chance in their lives to talk about these things with other people, or think about them because there was too much else going on in their lives for them to be able to process, and that building up over the course of a lifetime. And that having this as an intentional space where people were cared for, there was dinner, there was music, there were restrooms. They didn't have to be in survival mode and they could have these conversations. I think another thing you both mentioned is, a real earnestness for people wanting to get involved. There was a guy who came by one day and went, “Oh, I was walking by, what's happening? I just got off work. Actually, do you guys want a pizza? I got a pizza. Or anyway, do you have like a volunteer list or something I could help?” And then he came back several times. And just being able to get over that first hurdle of, here is a way that people can show up and then they will. Unless it's raining or there's wildfire smoke. We did get fewer people showing up for those. It was hard to breathe some of those times.

KC: And if I could just add, just some people who have been locked in their homes because of the pandemic and shelters-in-place. And I mean, we haven't talked about the COVID piece of it, but that really came into play. I think that some people were just happy to be vaccinated, and outside, and meeting people, which is something they had not done a lot of over the last past, you know, however long 2020 lasted at this point. I don't even know how long 2020 has been here. What is it, like 2022 already?

JM: I think it's been about three years.

KC: Exactly. You really saw people who had this hunger to meet people and to interact with people in a space that wasn't survival mode, mutual aid, the National Guard about to be outside in our front yard, you know? So yeah.

BO: How was the food provided?

QZ: In a little cart. The Midtown Exchange folks got us a real good deal on takeout from a number of the places there. It is a thing like, I wish that we had the ability and the capacity to cook and feed people, and we just could not organize that piece. But Midtown Exchange was great. And every time there was a dinner, there was this cart and they would roll it over and we would set it up and we would just hand it out. And when food was left over, we would leave it on one of the tables and say, “Please eat.” And it was always gone. I think one night we had extra extra, so we brought some over to an encampment or somebody loaded up in their trunk and brought it over.

BO: We are at the end of the questions and we are surprisingly on time. I have a last question of my own, maybe to conclude this. What is the museum doing here? Was it of any significance to you that part of the support for the project comes from the museum? Was there anything we could do that we didn't do? When you’re kind of looking ahead to the next year, how you can better use us and the resources of the museum to do what you need to do?

JM: I think the involvement of the museum shows a part of an ongoing change in what museums do and what their role is. Museums are facing the fact that they cannot be as they've classically existed, a space that is a repository of objects, that extracts objects from people and culture and holds these in objectivity forever. There needs to be engagement with communities, both in the creation of an acquisition of things and ideas. And I think classically museums have treated the space around them as just that, like it's physically where they are and not as a community that they are a part of or invested in. And I think the involvement of the Weisman is a promising trend in active—participation that is not extractive.

The museum did not come in with a, "Thanks for coming to our gallery. Now fill out this survey.” Or “What can you do for us to help us shape our 20-year equity plan?” or something. It was a very, I think a very hands-off approach of “Here are resources that we can leverage. We can leverage ASL interpreters, we can leverage these things and this space. Here you go, do something with it.” And I think there is in future years, potentially space for more active participation. I think that a space like the Weisman is not necessarily a place that a lot of the people at these dinners would see themselves as being welcomed in, let alone comfortable in or represented in. And I think there could be potential to increase those community connections, if that's what you want. But I think as it is, this was a very good way for an institution to offer resources, but not in a, “We're gonna do this for you, and now you're gonna round out our numbers so we can get a better grant or things like that.” It was community support, not community extraction.

QZ: The insurance alone was priceless for us. No, it was a pleasure to work with the Weisman and to work with you. From sending folks from the museum staff to build the... to work on the installation, to coming and being supportive, to just being another human set of hands, and a person with a car when we needed to get somebody back to the airport. Or just there's ways that I feel like the Weisman as an institution was able to help—providing the ASL interpretation, being able to front in the beginning when we didn't have money in the bank yet, providing the insurance. Also the legitimization of it by being like, “Oh, this is a Weisman project.” That opened a whole bunch of doors too. 'Cause people be like, “Oh, we need to take this seriously, it's connected to a museum.” But then also, what I appreciated about working with you in particular, Boris, is that you were also just a human being who was interested in helping. And sometimes that's actually all it takes is to like, be a part of the community that's pulling off and run to the office supply store, if that's what is needed, you know. We were all doing stuff like that. So, it wasn't like, “I'm only here to deal with the art. And I'm divorced from that as a human being.” It was showing up as a whole self. Yeah.

KC: Yeah, and like for me, it really did feel like the Weisman said, “No, we see what you're trying to do. We see that there needs to be some work around what you're talking about, you know. we see.” I mean, honestly South Minneapolis has been through a lot. They are in pain and like, “We can help, and this is how we can help.” And it felt like instead of it being this stuffy museum, it felt like as a member of the community, the Weisman came to us and said, “Hey we are too a part of Minneapolis, how can we help you?”

BO: Well, thank you all so much for doing this work. Thank you for giving us your time and knowledge this evening and in general. And I'm very much looking forward to seeing what you cook up for next year, next summer, and to learning how we can support you better in any way possible. Maybe you should have it as a point of discussion in your retreat, how we can use the museum?

QZ: You're on to us, you're on. It's fine.

BO: If you guys want to reach out to the Truth Collective, there is the email in the chat that I posted and they're also on Instagram, look them up. Send them money, send them love and thank you all.