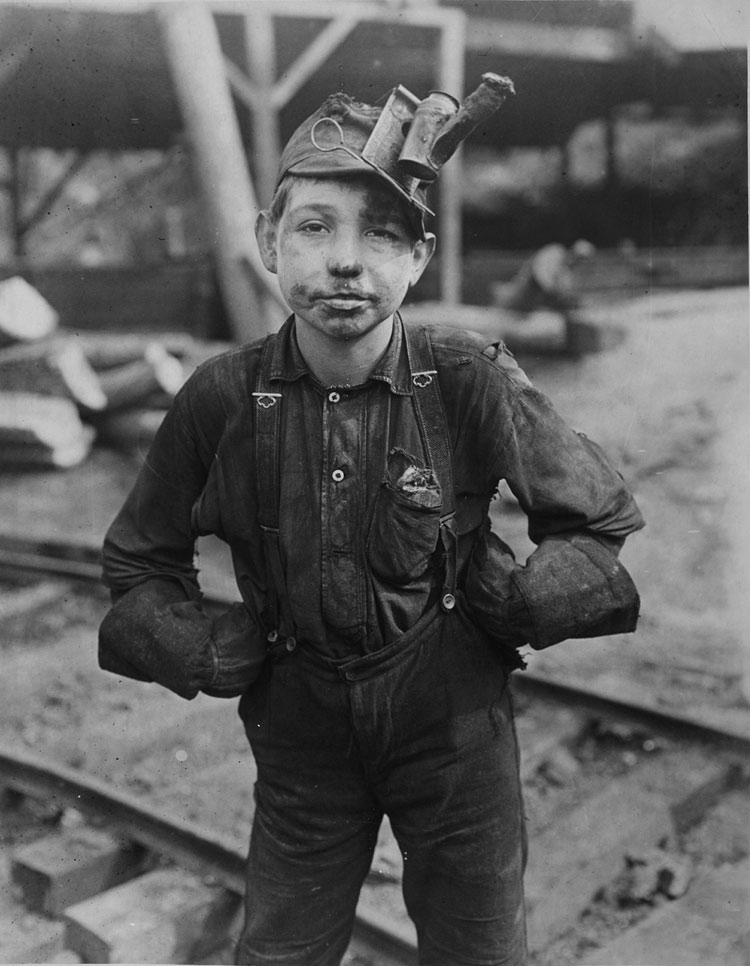

Young Boy Coal Miner, 1909-13

Photograph, 135/8 x 1011/16 in.

ABOUT THE ART

This is one of a series of photographs taken by Lewis Hine to show the condition of children working long hours in dangerous, difficult jobs. This boy, who looks to be ten to twelve years old, faces the camera, dirty and tired from working in a coal mine. His hands on his hips, he pauses a moment in his work clothes. The cap on his head holds a gas lantern with a large wick. In his pocket is a bag of chewing tobacco. He stands before railroad tracks that carry the carts of coal out of the mine.

Small boys were useful workers, being able to climb into the tiniest caves of the mine and light explosives. Besides not receiving an education or time to play, many young miners were killed or gravely injured in work accidents. Photographs like this of working boys and girls were published and shown by Hine to groups of people in order to raise awareness of this social problem. This photograph, along with several others by Hine, helped to convince a majority of Americans that child labor was unjust and resulted in laws to make the practice illegal in the United States.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Lewis Hine was born in 1874 in Wisconsin and lived in Chicago as a young man. In 1901 he moved to New York City to work as an assistant teacher at a progressive high school and to work on his college degree. He began to photograph school events and teach students about the technology of photography. Hine also became fascinated with Ellis Island and the struggle of new immigrants. His interest in using photographs to raise awareness of social issues led him to take an assignment from the National Child Labor Committee to travel and document the poverty and dangerous conditions faced by working children. He traveled and lectured, sharing his images with civic groups. His work influenced the later work of many photographers who saw the emotional and political power of photographs. Hine continued to work throughout his life, notably documenting the building of the Brooklyn Bridge and working at the end of his career for the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Hine died in 1940.

COAL MINING WORK

Coal is drilled, blasted, and dug from underground tunnels. In the early 1900s thousands of boys under the age of 14 were employed in coal mines in the United States. The risks of injury and death from cave-ins, fire, explosions, and gas poisoning were high. Other hazards included floods, dust-filled air, and machinery accidents. Boys younger than ten worked as “breaker boys,” picking slate out of the harvested coal. Hard-working boys could be promoted to the job of “door boy” or “mule boy.” Many boys took pride in this tougher work, proud to light a gas lantern on their cap and descend deep into the mine tunnels to work with the older miners. Door boys helped to control the ventilation and access to tunnels and mule boys were responsible for moving the coal cart out to the breakers. The next promotion was to laborer, and then the top job of miner.

CHILD LABOR LAWS

By the late 1800s states and territories had passes many laws regulating work conditions for children. But these laws were often ignored, particularly in poor communities or for immigrant families. In 1904 the National Child Labor Committee was organized by socially concerned citizens, and from 1908 to 1912 Lewis Hine photographed children working in several industries. As a result of his work, tougher laws were passed. In 1938 Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, better known as the Federal Wage and Hour Law. This law established a minimum wage and a 40-hour workweek, and banned children under eighteen from working in hazardous jobs, such as mining.

THE POWER OF PHOTOGRAPHY

Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis pioneered the use of photography as a tool for social change. They used images to influence emotion, draw attention to their concerns, and prompt political action. The photographic image was understood as true to life. Photography grew in importance as image-filled magazines like Look and Life grew in popularity. In the 1930s the U.S. government hired photographers to document the farmers struggling during the dust bowl years. These images were used to persuade the American people to support relief and social security efforts. Today we live in a world filled with photographic images. We are more aware of how they can be altered and used to convey messages and not necessarily objective truth. Artist Gordon Parks famously said that a camera was his “choice of weapon,’ recognizing the power of his images to influence hearts and minds.