On Gallery Guards and Audience Engagement

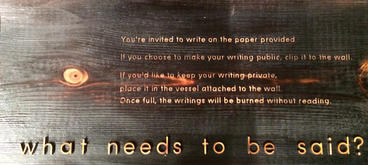

While examining Krinke’s work I find a certain restriction in observing the visitor’s interaction with the piece. In this post, I hope to examine the indirectly look at the interactions of the visitors through an altogether different source, the gallery guards. I hope to spotlight the effort of the often overlooked force of the museum, the gallery guards, examining their interactions with Krinke’s piece and the visitors who activate it. Since beginning this project, I’ve been interested in the ways in which these (for the most part) silent members of the museum interact and respond to the Rebecca Krinke’s piece What Needs to be Said.

In 2013 the New York Times ran an article titled Varied Duties, and Many Facets, in a Guard’s Life: Museum Guards on Life Beyond the Galleries, in which the Time’s current Opinions Editor, David Wallis, interviewed gallery guards from various institutions including the Guggenheim, National Museum of the American Indian, and Minneapolis’ very own Walker Art Center. Inspired by Wallis’ write-up, I decided to do some investigating into the life of WAM’s guards and find out how they’ve experienced What Needs to be Said.

Methodology:

I opted for the infamous Google Forms format of collecting responses from the guards. The method, while often treated with a well deserving eye-roll, provides the most anonymous and hence a more open and honest response from the participant. I asked the following 5 open-ended questions:

(1) Is there anything you want people to know about your position?

(2) Do you find yourself constantly engaged with the visitors? Has this engagement yielded any memorable moments?

(3) What attracted you to the Gallery Guard position?

(4) Do you find your engagement with visitors heightened when you are around Rebecca Krinke’s piece (What Needs to be Said)? If so, how?

(5) Can you tell me anything about the ways in which visitors have interacted with Rebecca’s piece?

Analysis of the responses:

(1) The consensus is quite clear: the work is not the most riveting experience. You’re on your feet for hours, deal with boredom, and often respond to “not so pleasant members of the general public.” However, later responses reveal a greater overarching meaningfulness to the experience.

(2) As far as visitor engagement, perhaps a lesser known position of the guards is their visitor services responsibility. However, the guards occasionally do spend up to 8 hours at the museum. As far as memorable moments, answered range from: “My most memorable moment was connecting with the choreographer of the Rio Olympics opening ceremonies and hearing her interpretation on our collection.” to “The most memorable moment was at the Cajal exhibit opening when a woman I had never met just sang at me for a full minute. Didn’t say anything, just made eye contact and sang.”

(3) For those choosing the position, the largest interest was to work within the museum setting. One response stressed the interest in an ability to be in a meditative state. However, the responses all stressed the proximity to an art-centered institution as a way of facilitating a relationship with the museum.

(4) Here, the response was not as definite. There appears to be interactive level between the guards and the visitors. Some visitors appear uncertain about intervening in the installation, in which case the guards act as sources of instruction and support. On the other hand, some guards find themselves in a more passive position of observing meditative visitors. Here, I find a parallel between Claire Bishop’s Artificial Hells, particularly in the sense of the uncertainty of the visitor’s level of appropriate engagement within the seemingly sacred institution that is the museum. However, the guards then breach this confusion by providing an instruction to the navigation of the piece.

(5) As far as specific interactions visitors have had with What Needs to be Said?, all of the interviewed guards noted a widespread interest in the work. Through their position, they observed that visitors to the museum don’t act passively towards the piece, but rather, are compelled to participate in What Needs to Be Said. One guard pointed out the tendency of the visitors to engage with the public component in comparison to the private vase portion of the work, an interesting observation which needs further pondering on in a future post. The guards remarked different notes they saw visitors pin, one reading “I wish my family would get along with each other.” Among the messages of positivity and encouragement, these particular messages stand out. Which goes back to my first post’s final question—what is our role as readers? How do we respond to messages which bare a certain level of urgency? Perhaps you have an idea? Feel free to respond in the comment section.

Conclusions:

Functioning in a museum setting, Krinke’s What Needs to be Said, relies heavily on the presence of gallery guards. While the guards by the virtue of their name act as the protectors of the museum’s walls, the participatory nature of the piece calls for another level of interaction. When stationed at the Target Gallery, the guards often function as points of instruction. Without the presence of the artist, the guards aid the occasional disorientated viewer enabling them to become a participant. As the piece relies on voluntary participation, the guards assist those who seek help in navigating the piece. From listening to the guards, it is clear that, as a result of this role, the guards retain certain experiences in the museum; some visitor interactions embed powerful emotions.

As the human face to the museum, the guards maintain order and represent the institution. Their days may feel long but they hold special access to institutional knowledge and they pick up on those moments between art and the visitor that maintain the museum as a sacred site.