Jim Denomie was a University of Minnesota art student when he began the work of re-claiming his tribal heritage and re-connecting with his Native identity. Nearly twenty years later, he is nationally known for his humorous, critical depictions of United States history and religion. His paintings address colonization, assimilation, white washing, and other violences that the Native population has suffered at the hands of Western European colonizers.

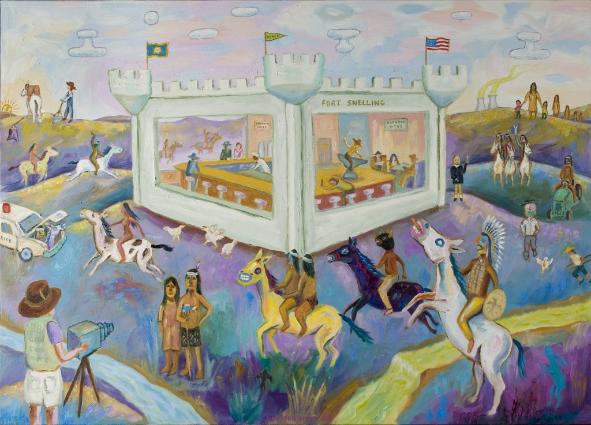

Denomie currently lives in Franconia, MN while his work resides in collections all over Minnesota and throughout the greater United States. His 2007 painting “Attack on Fort Snelling Bar and Grill” is currently on display in the Weisman Art Museum’s Silver River. I recently caught up with the artist to talk about the work, the rivers, and his artistic practice in general.

EA: Can you tell me about the narrative or impetus behind your 2007 painting Attack on Fort Snelling Bar and Grill?

JD: The inspiration for Attack on Fort Snelling Bar and Grill came from my wife’s, Diane Wilson, involvement with a historical event. Around 2004, as she was doing research for her memoir, Spirit Car, she became aware of a group of native educators who were organizing a march to commemorate the forced march of elders, men, women and children from Mankato, MN to Fort Snelling during a brutally cold November in 1862. Many people died during the weeklong march and over three hundred died in the winter incarceration camp below Fort Snelling on the banks of the Mississippi River. Some people believe that this ugly history makes Fort Snelling a prisoner of war camp and should be demolished.

EA: Fort Snelling is located at the junction of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers, which are both depicted in Attack on Fort Snelling Bar and Grill. Did you include the two rivers in order to locate the scene geographically or is there a significance to their presence in the piece?

JD: I did include both the Mississippi and the Minnesota rivers to locate the scene geographically.

Both rivers are important to me personally and culturally. As a boy, I used to play on the banks and swim and fish in both rivers. I still visit the rivers to relax and to just sit by the water. Culturally, the Annishinabe (Ojibwe) my tribal affiliation, navigated the lakes, rivers and streams in the Great Lakes area by birch bark canoe including the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers.

EA: Why do you feel that it is important for you to depict historical scenes in your paintings?

JD: When I started painting at the University of Minnesota in 1992, I just naturally portrayed storytelling. Storytelling is used in Annishinabe culture to pass on knowledge from one generation to the next, preserving culture and history. As a student at the U, I also studied U.S. history. I learned about the history between the Federal Government and the native people of this continent. I saw how historical events and government campaigns shaped our current situation today. I learned about the treaties and how the reservation system was developed. Most importantly, I learned how this history shaped my personal identity. Some of these historical events (and my understanding of them) became subject matter for my paintings.

EA: What role do you see art playing in political resistance and activism?

JD: I am not sure how art will play a role in political resistance and activism. I don’t think many artists approach an event in those terms. Of course there are the exceptions. I paint about historical and contemporary events to educate people. I suppose that is a form of activism. Even now, I am making sketches of the protest near the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota opposing the construction of an oil pipeline that threatens the safety of the Missouri River. In the past few months, thousands of people have traveled to North Dakota to support the Standing Rock Sioux. Some of these sketches will become paintings and some will be studies for a larger narrative painting about the developing event and it’s conclusion. Hopefully, the sketches and paintings will be exhibited, or published in print or on the web, possibly informing people (who may or may not know of the protest) of the event and how I perceive it.

Silver River is open at the Weisman Art Museum from Saturday August 13, 2016 to Sunday February 12, 2017. Click here to find more information on the show and related programming. The Weisman Art Museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10 am to 5 pm and Wednesday evenings until 8 pm.