"Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" is a new WAM Collective blog series highlighting the overlooked and underrepresented artistic contributions of American artists. The title of the series references a 1971 essay of the same name by art historian Linda Nochlin, which examines the institutional boundaries that have prevented Women artists from succeeding in the arts.

Featuring work by artists of color, women artists and LGBTQIA artists and sharing the narratives that have been erased or forgotten over time, this series seeks to introduce our readers to works by great artists who succeeded despite the institutional boundaries and oppression that they faced.

You may have seen her as the recently featured Google Doodle, but who really was Edmonia Lewis? In addition to being the first African American woman to gain international prominence as a sculptor, her works also inspired the early feminist movement. Unlike most neoclassical subjects popular at the time, the subjects of her works also dealt with themes of emancipation and freedom, specifically as they related to women and Black Americans.

Early Life

Mary Edmonia Lewis was born in Greenbush, New York in 1844. Her father was Afro-Haitian, and her mother was part African American, part Mississauga Ojibwa. Her parents died by the time she was nine, and she and her half-brother Samuel were adopted by her two maternal aunts, who raised them in the Native American community.

Education

Because her mother worked as a weaver and craftswoman, Lewis was exposed to hand crafts at a young age. Samuel went out to San Francisco during the gold rush, and was able to make enough money to finance Lewis’s schooling. She first went to New York Central College, and later attended the ladies' preparatory program at Oberlin College in 1859 where she began studying art. While at Oberlin, she faced severe discrimination. She was falsely accused of poisoning her two white roommates, and although she was acquitted, she was severely beaten by a mob of local residents. Later, Lewis was falsely accused of stealing art supplies and not allowed to graduate.

Early American Works

Refusing to be deterred by the unjust treatment she received while in school, Lewis moved to Boston in 1863 with the intention of becoming an artist. Here, she was introduced to William Lloyd Garrison, Lydia Marie Child, Charles Sumner, John Brown, and other prominent abolitionists. Working with abolitionist and portrait artist Edward Brackett, where she learned the art of clay sculpting, allowed her to create busts and portrait medallions, allowing her to make a decent living, which was unheard of at the time.

Migration to Rome

By selling the works she made in Boston, Lewis was able to save up enough money to travel to Italy. In 1865, just two years after she started working in Boston, Lewis sailed to Florence, where she was met by American sculptor Harriet Hosmer. Once in Italy, Lewis joined the social circle of American actress Charlotte Cushman, Hosmer, and her companions. Moving abroad helped American women emancipate themselves from the social constraints they were forced to endure there, allowing themselves to reach their full potential. Here, women were able to exercise their independence financially, artistically, and sexually.

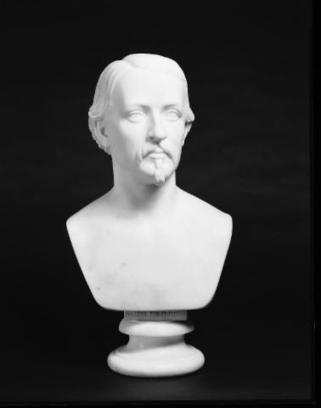

After six months, Lewis moved to Rome, renting a small studio once owned by neoclassicist Antonio Canova, where she taught herself how to carve marble. Unlike most sculptors, who employed the use of assistants, Lewis did everything herself for fear of others questioning the authenticity of her work. While in Rome, Lewis befriended cultural icons such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Franz Liszt, whose busts she created.

Lewis catered to the interests of American collectors, sculpting busts of prominent Americans such as Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Senator Charles Sumner, and the poet Anna Quincy Waterston. Her works were broadcasted in Harper’s Bazaar, allowing her to reach international acclaim. By the 1870s, her studio was listed in popular guidebooks, making it a popular stop for American tourists. She later went on a cross-country tour of the United States unaccompanied, shattering cultural norms for the time.

Notable Works

Now on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Lewis’s life-size statue depicts the biblical woman Hagar, who served as the slave of Sarah, the wife of Abraham. When Sarah could not conceive, she granted Hagar permission to have a child with Abraham in order to preserve the family lineage. When Sarah eventually had a child with her husband, Hagar and her son Ishmael were freed, but forced to suffer a life of ostracization.

The biblical figure of Hagar had often been used by neoclassical artists to represent slavery. Indeed, this theme was extremely meaningful to Lewis, as she herself suffered racial violence and banishment during her college years. In a larger context, Hagar speaks to the alienation of all black women in American society. Lewis later stated that she had “a strong sympathy for all women who have struggled and suffered.”

Also on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Old Arrow Maker uses classical Greek and Roman style of sculpture to represent the characters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “The Song of Hiawatha” in an idealized manner. “The Song of Hiawatha” takes place along the shores of Lake Superior, and recalls the life of mythical Ojibwa hero Hiawatha and the lessons he taught his people, as well as his love for Minnehaha.

This scene depicts Minnehaha in her wigwam with her father as she waits for Hiawatha to ask for her hand in marriage. In this work, Lewis represents Minnehaha using idealized conventions, but broke barriers by representing her father, the arrow maker, using idealized but recognizable Native American features. In Old Arrow Maker, Lewis portrays Native Americans as tranquil, proud, and dignified differed from popular representations of the time, which often showed Native Americans (and African Americans) as eroticized savages. This work also held personal significance to Lewis, who was raised by Ojibwa women.

Legacy

By the late 1880s, romanticism had replaced neoclassical sculpture. Lewis fell out of prominence and remained in Rome until her death. However, her life was still extremely inspirational to many. Although her works often adhered to traditional western standards or history and beauty, she did not. Not content to live and work in the domestic sphere, Lewis never married, and supported herself her entire life.

The life and works of Lewis had profound influence on Francis Willard, one of the pioneers of the early feminist movement in America. She took Lewis depiction of the slave’s marginalization within society and used it as a metaphor for white women living under the patriarchy. Lewis work and ideas to early feminist movements in America, although as with the contributions of many women of color, their contributions are neglected or attributed to white women.

Sources

Salenius, Sirpa A. "US-American New Women in Italy 1853-1870." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 14.1 (2012)

Regenia A. Perry Free within Ourselves: African-American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art in Association with Pomegranate Art Books, 1992) http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artist/?id=2914

Rivo, Lisa E.. "Lewis, Edmonia." African American National Biography, edited by Ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr.. , edited by and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. . Oxford African American Studies Center, http://hutchinscenter.fas.harvard.edu/lewis-edmonia-c-1844%E2%80%93after-1909-sculptor